Escaping the Heat of the City in China

By Chris Courtney

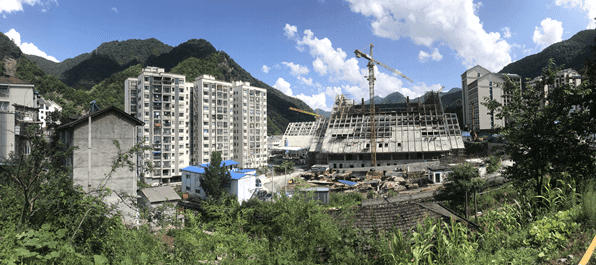

A construction boom is underway in the mountains of western Hubei. The mountainous forests of Shennongjia 神农架 are one of the least developed regions of China. As such, they remain home to vast array of plant and animal species, including, as legend would have it, the elusive yeti-like creatures known as wild people yeren 野人.

In recent years, the once sleepy towns in this region have been filled with construction cranes and concrete lorries, catering to a rapid influx of newcomers. They hail, almost exclusively, from the city of Wuhan in the east of the province.

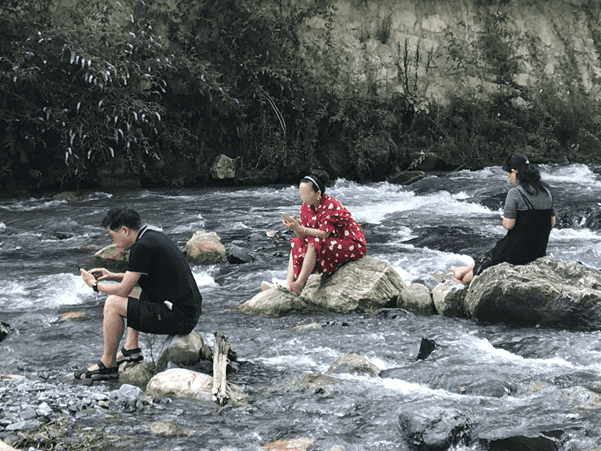

Shennongjia has many attractions for these urban sojourners. Here they can enjoy fresh food purchased directly from farmers and breathe air free from pollution.

Yet their primary motivation for undertaking the 500 km journey to the mountains is to find a cool place in which they can spend the summer away from the infamous heat of their home city.

Their annual urban to rural pilgrimage is, perhaps, indicative of an emergent pattern of seasonal migration, one that may well become increasingly common throughout Asia and the world as rising temperatures make cities inhospitable to live.

At the same time, relatively wealthy people retreating from the city heat to countryside areas has a deeper history in China.

Rapid apartment and hotel construction in Shennongjia, Hubei, 2019. Photo by author.

Historically, very few people in China could indulge in the luxury of abandoning their homes just because it was too hot. If they migrated regularly then it tended to be in search of work. Rural migrants flocked to cities, for example, during slacker periods of the agricultural year. There were some groups, however, that did possess sufficient wealth to migrate when temperatures got too high.

The Kangxi Emperor (1654 - 1722) named the vast complex of palaces and gardens that he constructed at Rehe 热河 his Mountain Estate for Escaping the Heat 避暑山庄. Despite what the name suggests, this summer capital was probably more important in terms of its political and ritual functions rather than as a refuge from hot summers.

After all, the temperatures at Rehe – known today as Chengde 承德 - were not as significantly lower than those at Beijing. It was, in fact, while hunting and sleeping under the stars in their Manchu homeland further to the north that the Qing court could truly appreciate a cooler climate.

Rehe xing gong quan tu 热河行宮全图, Panoramic view of the Rehe Imperial Palace, 1875-1900. Source: Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.

The heat and humidity in Beijing pales in comparison to that found in the "great furnace cities" 大火炉 of the middle and lower Yangtze region. For the Europeans who began to settle in this region in the nineteenth century, this climate was considered not just uncomfortable but injurious to their physical and mental wellbeing.

During this era of imperial expansion, British scientists and officials had developed a series of theories that linked race and climate. Many had become convinced that members of the so-called white race could not survive long-term residence in a hot climate. This had led imperial officials in India to develop a number of hill stations, where they could enjoy the relatively cool temperatures during the summer months.

Though China was not subjected to the same form of formal imperialism as India, Europeans adopted a similar set of strategies to cope with the oppressive heat. In the 1890s, having endured several years living with his family in the stifling humidity of the middle Yangtze plains, a missionary called Edward Little became convinced that soon at least one of his children would perish.

To avoid this fate, he invested in an estate on Lu Mountain 庐山 in Jiangxi. With a nod to its function as a refuge from the heat, Little called his new estate Kuling 牯岭, a pun on the English term "cooling" which could also be pronounced in Chinese (as Guling). Before long Europeans from throughout the Middle Yangtze region were flocking to this mountain resort in the summer months.

An advert for the Kuling Resort, early twentieth century. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Though Kuling was initially an exclusive enclave reserved for European and American settlers, by the 1930s members of the Chinese political elite could also be seen being carried up the mountain in chairs. Eventually the premier Chiang Kai-shek, who had been introduced to the resort by his wife Song Meiling, transformed Kuling into his summer headquarters, providing the upper echelons of his Nationalist government with a means to escape from the furnace of their Nanjing capital. Despite an avowed desire to overthrow all forms of bourgeois privilege, after 1949 the Chinese Communist Party retained Kuling as their summer retreat – indeed, Mao took over his old rival Chiang’s personal villa on the mountain. At the height of the summer in 1959, the Party held its infamous Lushan Conference at the resort, during which Mao vigorously rejected criticisms of the disastrous Great Leap Forward. While millions starved in the burning heat of the plains below, Party leaders enjoyed the cool luxury of an exclusive mountain resort.

Urban tourists enjoying a cool river in Shennongjia, 2019. Photo by author.

Like the towns of Shennongjia, today Lushan is a popular destination with Chinese tourists seeking to escape from the heat of the city. The old European villas have been converted to hotels and restaurants. In one sense this represents a continuity with the past. Yet at the same time, as incomes have grown over the past few decades, these refuges from the heat are no longer reserved for a privileged few. The numbers seeking sanctuary are only set to grow, as the urban heat island effect makes cities increasingly inhospitable, especially for the young and elderly, who dominate the tourists found in Shennongjia. Thus, a pattern of what we might describe as satellite urbanisation has emerged, whereby city dwellers colonise cool areas of the countryside. This is often at the expense of local inhabitants, who are priced out of the housing market by the newcomers. With increased mobility and heightened lifestyle expectations, cities are expanding well beyond their territorial boundaries into these satellites. As the forests of Shennongjia are cleared for hotels and apartments, some local inhabitants claim to have noticed a broader shift in the local environment. "I never wore short sleeves before," one resident remarked to me, "I think it’s getting hotter here since all these people arrived from the city."