Fire and the Problem of Urban Heat

By Fiona Williamson

The possibility of fire in historic urban Singapore was an ever-present threat. With many houses built from natural materials including attap and wood for much of the nineteenth century with, as Caitlin Fernandez explains in this section, pockets of old-style housing until even the late-1960s, Singapore was highly combustible.

It is perhaps hard to imagine a city with a tropical climate as being so flammable, but the region was (and is) also prone to long, hot dry periods. The streets would be filled with dust and the grass, weeds and even some adjacent jungle would become tinder-box dry.

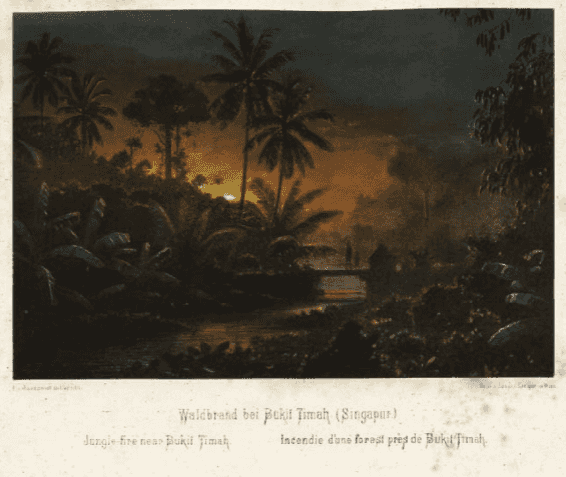

Jungle Fire Near Bukit Timah, from Skizzen aus Singapur und Djohor by Baron Eugen v. Ransonnet-Villez, 1876. Collection of National Library, Singapore. [Accession no.: B03013662J]

Jungle clearances and droughts compounded the problem, the latter leaving little water available to douse fires, let alone drink. In 1877, for example, there occurred one of the worst droughts then known in the living memory of Singapore’s inhabitants.

Wells, streams, and rivers dried up or became fetid, plants died, and the heat made everyone miserable. Fires increased in frequency.1 One of these narrowly escaped becoming a major disaster, when an incendiary from the military barracks at Tanglin fell into a neighbouring garden, setting the grass alight.

With the fire spreading around the house and the wind blowing back in the direction of the barracks officer’s quarters, the situation looked dire. Fortunately, John Baxter, the bungalow’s owner, was in the middle of rebuilding works and all the on-site workmen rushed to help him douse the flames.2

Such luck had not been present earlier that year however, when there had been a disastrous and costly fire at the Tanjong Pagar docks. The docks were home to various small industries and storage facilities for goods and materials, including coal. The coal was stored in wooden sheds covered with attap, possibly the worst possible combination of materials.

The exact cause of the fire is unknown but there was some suggestion that a stray spark from a carpenter’s pipe set light to wooden shavings underfoot. The ‘great heat and drought’ had left the area dry as a bone and the sparks quickly turned into flames that spread to the coal sheds, fanned by a strong north-east breeze.3

The fire-brigade responded fast, but the drought had hit the town’s water reserves hard. There was almost no pressure and their hoses produced little more than a thin stream of water. After three hours of trying to manage the conflagration, the Royal Artillery were despatched from Fort Canning to assist, along with two army companies, and the crews of five nearby Royal Navy ships.

By that evening, all the wood and attap buildings had been destroyed and most of the coal had gone up in smoke. The irony is that the main pumping station for the town’s water was coal powered. The coal then stored on the docks was the station’s main supply, a fact that only compounded the water shortage during the drought.

Illustration of the Great Fire at the Tanjong Pagar Wharf (1877). Source: Forty good men - the story of the Tanglin Club in the island of Singapore (1865-1990).

Heat and dry weather continued to be key catalysts of conflagrations in Singapore town. In 1907, for example, ‘a fire broke out in the jungle and brushwood on the piece of waste ground between Bidadari cemetery, on the Serangoon Road, and the junction of McPherson Road’. It was soon realized that ‘a row of shop-houses on the Serangoon Road … were in danger’ so the police were called.

On the spot were one Inspector Crummey and his assistants, who ‘attached a couple of lengths of hose to a hydrant and drenched the attap roof of these buildings’. The fire continued to spread however, so the fire-brigade had to be summoned to assist ‘the police in saving the houses’.

The cause of the fire was attributed directly to the ‘recent hot weather’ that had ‘made the jungle and undergrowth very dry so that the flames spread with great rapidity.4

Likewise, in the 1930s, a series of grass fires occurred within quick succession, especially in waste grounds filled with lallang [a weed-like grass] at Telok Blangah, Joo Chiat, River Valley, Somerset Road, Mount Pleasant, Outram Road, and the old race-course. These were all attributed to spontaneous combustion in the ‘terrific hot weather’.5

During the late 1940s, lallang blazes destroyed about an acre of land at Telok Ayer. For a hair-raising moment, it looked as though the flames ‘threatened one of the many godowns … but [they] were gradually put out by firemen using buckets of water’.6

Two days later, the ‘prevailing hot weather’ was believed to have caused two more lallang fires on the outskirts of Singapore. ‘Four to five acres of lallang, beside the Admiralty Oil Farm, at the 4½th Milestone, Ayer Rajah Road, were burnt in a fire which broke out at 4.30pm.’ In the other fire, lallang at the RAF Aerodrome, Changi, was set alight. The Singapore Fire Brigade was called to put out the fires in both instances.7 The following year, a heat wave catalyzed a string of outbreaks:

"The very hot weather coupled with the leaving of lighted joss sticks at Chinese cemeteries caused most of the 22 fires attended to by the Singapore Fire Brigade during the last four days. The heaviest day for the Brigade was Sunday, when there were 10 fires, 8 of which were grass fires at or near Chinese cemeteries ... Yesterday was another heavy day for the Brigade when 5 fires were attended to up to late afternoon. Most of these were also grass fires. There were 4 grass fires on Saturday, 1 of which at Bukit Brown Cemetery, took four hours to subdue. There were 2 grass fires on Friday."

— in The Straits Times8

The historic archive is littered with similar accounts of heatwaves and dry weather causing spontaneous and frequent fires.

Nowadays urban Singapore is well-managed and the city boasts an excellent fire service.

However, as urban temperatures rise due to global warming and the Urban Heat Island (UHI) effect, these tales from the past serve as a timely reminder of the additional stress that heat may well place on Singapore’s resources and services in the future.

- ‘Variorum’, Singapore Daily Times, 31 May 1877, p. 3.↩

- ‘Untitled’, The Straits Times, 24 November 1877, p. 3.↩

- ‘The Great Fire at Tanjong Pagar Wharf’, The Straits Times, 14 April 1877, p. 2.↩

- ‘A Jungle Fire’, The Straits Times, 11 February 1907, p. 7.↩

- ‘Grass Fires’, Malaya Tribune, 5 February 1935, p. 13; ‘Lallang Fires’, Malaya Tribune, 5 August 1935, p. 12.↩

- ‘Lallang Blaze at Telok Ayer’, The Strait Times, 24 July 1947, p.7.↩

- ‘Two More Lallang Fires in Store’, The Straits Times, 26 July 1947, p. 3.↩

- ‘Heat Wave Brings Fires in Singapore’, The Straits Times, 6 April 1948, p. 7.↩