Heat as Experience: Snapshots from Indian Cities

By Ashawari Chaudhuri

Heat is a single word, but its experiences are multiple. As a standalone category, it is difficult to generalize about heat because it is often experienced with other conditions like humidity or dryness. Even within India, stifling, scorching heat in Kolkata, for instance, is different from the dry, blistering heat of New Delhi. Further, heat is endured differently, depending on the class, race, gender, age or caste positions of a person.

Memoirs and memories of rulers and ruled, and of well-known and ordinary lives in history are rife with descriptions of heat. As early as the 1500s, Babur, who claimed to have established Mughal rule in the sub-continent, wrote about heat in his memoir, Baburnama. While describing his journey and conquest of Kabul and then India, he wrote:

"Three things oppressed us in Hindustan, its heat, its violent wind, its dust. Against all three, the Bath is a protection, for in it, what is known of dust and wind? And in the heats it is so chilly that one is almost cold…"

— Zahiru’d-din Muhammad Babur1

Throughout the Mughal period, everyday lives of the community were infused with measures to withstand adverse weather conditions. Passive cooling methods in Mughal architecture like lattice work in buildings, gardens with water bodies, and using khus (vetiver) tatties were introduced to manage the microclimate of a space.

A seated Mughal court attendant in a garden. Gouache preparatory painting by an Indian artist, Mughal period. Source: Wellcome Collection

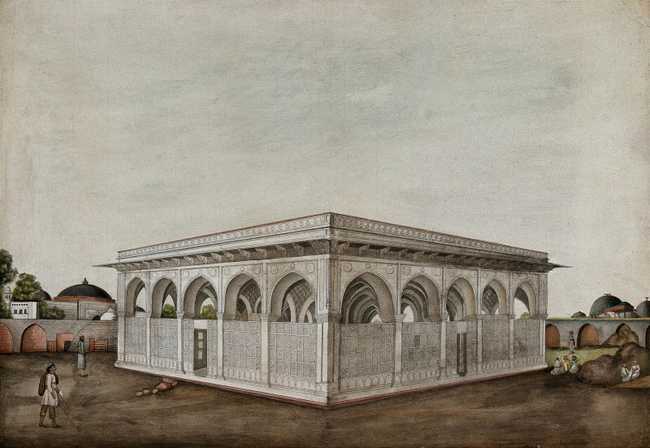

Men sitting and standing outside a Mughal mausoleum. Gouache painting by an Indian painter. Date: between 1800 and 1899. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Unlike the Mughal emperors, who had some experience with heat in Iran and Kabul, for the European and British colonialists, heat in South Asia was novel and baffling at the same time. As historians have written, until the eighteenth century, India was still largely a mystery for most Europeans because their interactions were primarily with traders who were based on the coasts, especially in the western parts. They hardly had any sustained contact with the hotter central parts of the subcontinent.2

Extensive commercial engagements and the eventual possibility of colonizing created for the British a slow but steady evaluation of the landscape, air, rivers, and climate. There were questions about whether bodies that were used to the cold, damp climate of England, for example, would be able to acclimatize with the Indian environment. It was in the nineteenth and the early twentieth centuries that the climate of India, especially the heat, was considered as not only different but inferior to England’s cold. This hierarchy, where tropical heat emerged as inferior to the temperate and cool climate of England, was entwined with others like those between the colonizer and the colonized, or European and native bodies.

Heat formed an important part of research on tropical medicine during the colonial period. Use of hand-maneuvered, cloth ceiling fans called punkah, and retreat to the hills during the peak of summer, were two of the main ways the British developed of dealing with the heat in India.

Lord Hardinge’s Residence at Simlah. Photo by C.R. Francis. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Although heat has always been a part of the South Asian environment, the increasing number and intensity of heatwaves in Indian cities have sparked a renewed interest in studying people’s experiences with heat. Rising heat levels have been especially difficult for labourers who have to work regularly under the blazing summer sun, and for women who spend considerable time around the fire for cooking.

In a study conducted by Ray et al on long term changes in mortality due to extreme weather events (EWE), the authors show that mortality rates in India due to heat waves have increased significantly in the past two decades. The study was based on data from the Indian Meteorological Department and traced mortality rates from different states over the past 50 years (1970-2019)3.

Although floods and cyclones have historically caused the most deaths due to EWEs, their lethality has decreased over the years. Heatwaves, on the other hand, have increased by 24% in 2010-19 compared to 2000-09, leading to an increased mortality rate of 27%. Mortality due to heat waves has been the highest in Andhra Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Odisha, Bihar, and Rajasthan.

A Hyderabad market on a sweltering evening. Photo by Srujan Meesala.

New Delhi has been one of the worst affected cities in the recent past. Temperatures there rise above 50 degrees Celsius for a significant number of days during the summer months. The city has even witnessed the uncanny phenomenon of some of its asphalt roads melting.

Experiences of extreme weather conditions in New Delhi are further exacerbated by frequent power cuts across the city. This is caused by increased demand for air conditioners that place an extra burden on the energy infrastructure. A resident narrated her experience of a quotidian day in the city:

"It was a typical morning in New Delhi. I took this picture from my apartment after spending half the night on the terrace because of a power cut. People here who live in barsatis and makeshift housing arrangements are familiar with this experience. The sun rising, although it meant another round of heat, does end the dark. I somehow find heat more unbearable in the dark."

— Amrita Datta

A midsummer morning in New Delhi. Photo by Amrita Datta.

Young boys bathe on a hot day in New Delhi. Photo by Ibrahim Rifath. Source: unsplash.com

In coastal cities like Mumbai, Chennai, and parts of Goa, the humidity adds considerably to the experience of heat. Heat and humidity together lead to high "wet-bulb temperatures" or the lowest temperature at which something can be cooled through evaporation. In drier places, one can sweat in order to cool down. But in more humid places, that option becomes restricted. This phenomenon makes it unsafe to do most physical labour4. Sometimes, the evenings bring respite from the heat as people spend time by the beach.

A regular day in Chennai. Photo by the author.

Three women chatting by the beach in Goa. Photo by the author.

Not just for people, beaches can be a refuge from the heat even for non-humans…

At a beach in Visakhapatnam. Photo by Srujan Meesala.

The increasing temperatures in cities across the world are a topic of urgent discussion. Yet the experiences of heat go far beyond its measure. Living and working with heat is significantly more difficult for those who do not have the privilege or the possibility to be indoors during the day. In Indian cities, where heat has always been interwoven with lives and stories of people, they find everyday, makeshift ways to shelter themselves from it. Whether these strategies are sustainable as temperatures rise further, however, remains to be seen.

An evening near Guwahati. Photo by the author.

A monk rests after a long walk in Haridwar. Photo by the author.

- Zahiru’d-din Muhammad Babur. Baburnama. A Memoir. New Delhi: Rupa Publications(2017) pp. 959.↩

- Harrison, Mark. Climates and Constitutions: Health, Race, Environment and British Imperialism in India, 1600-1850. New Delhi: Oxford University Press (1999). Reviewed by Warwick Anderson. Journal of Political Ecology, 9(1), 7-8.↩

- Ray, Kamaljit, RK Giri, SS Ray, AP Dimri, M Rajjevan, "An assessment of long-term changes in mortalities due to extreme weather events in India: A study of 50 years’ data, 1970-2019", Weather and Climate Extremes, Volume 32 June 2021: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S221209472100013X↩

- "What if a deadly heatwave hit India?", The Economist (3 July 2021) https://www.economist.com/what-if/2021/07/03/what-if-a-deadly-heat-wave-hit-india↩