Post-WWII Fire Hazards in Singapore's Kampongs

By Caitlin Fernandez

Before high-rise HDB flats, Singapore’s housing landscape was dominated by rural and urban villages called kampongs.

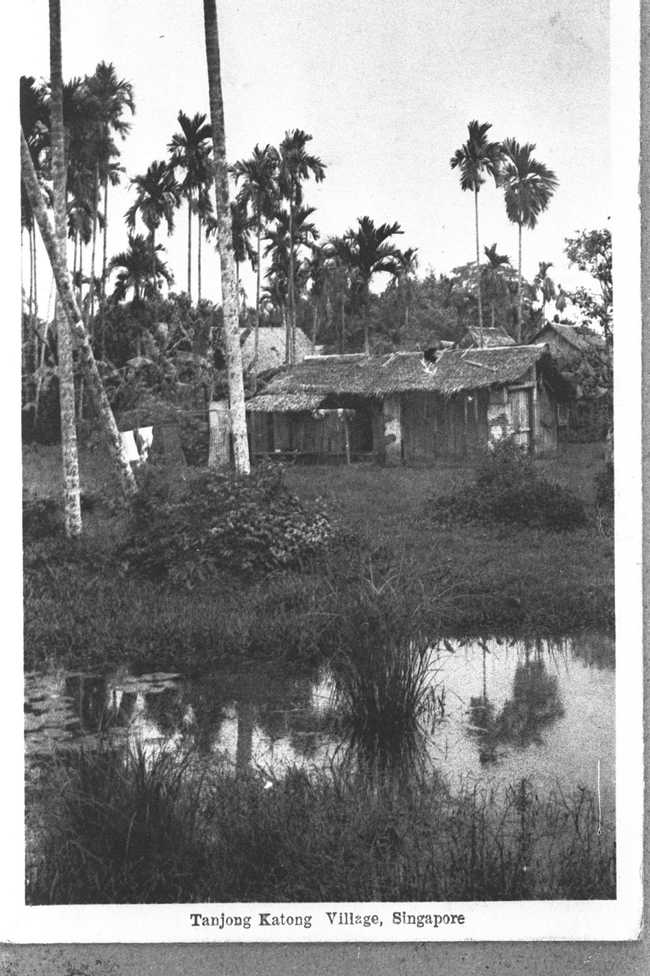

Rural kampongs were early fishing villages that were located along the coasts and river as well as some that developed inland and involved the cultivation of coconuts or fruits.1 There were Malay-style and Chinese-style kampongs, the former concentrated in the eastern and western parts of Singapore.2

The image above captures a rural Chinese kampong house with plank walls and attap roofs in Tanjong Katong Village, taken in the 1920s. Source: National Archives of Singapore, Media Image No: 19980005882 - 0102

Urban kampongs were newer to Singapore’s urban landscape, having flourished in the post-WWII period due to war-time displacement, accelerated immigration rates, and a "baby-boom".3 Also known as city-fringe squatter settlements, urban kampongs consisted of unauthorised squatter huts and shacks. They were located on the edges of the Central Area in: Siglap, Lorong Tai Seng area, Sims Avenue and Paya Lebar, Kallang Basin, Toa Payoh, Kampong Chai Heng, Farrer Road area, Tiong Bahru, Pasir Panjang and Telok Blangah areas.4

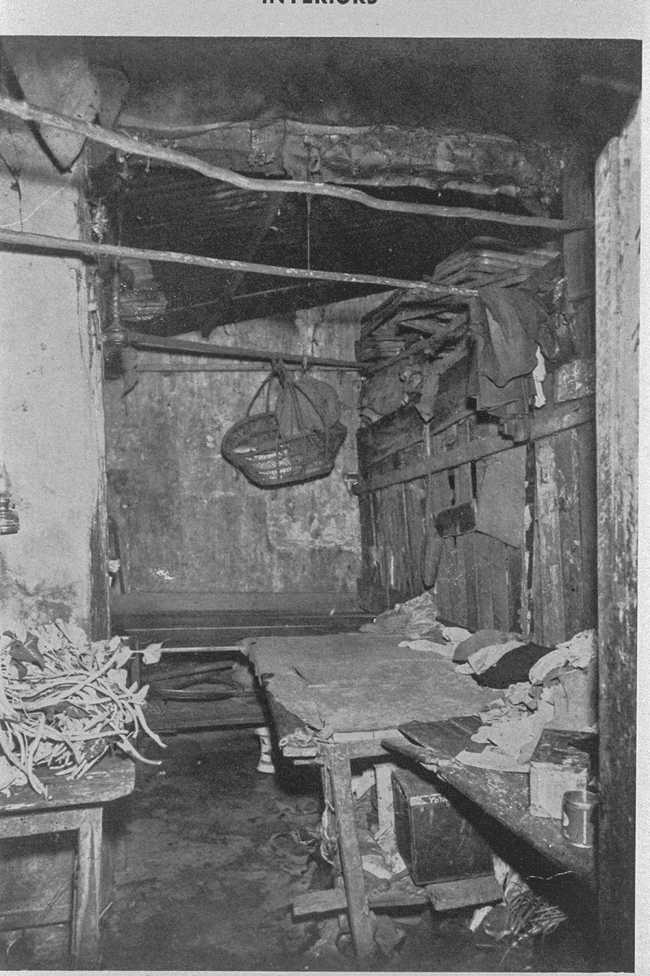

Most of the huts in these settlements had cement or wooden floors, wood-plank walls, and an attap or corrugated zinc roof.5 The huts were often tightly-sandwiched to one another, with each hut being further subdivided into cubicles.6

The image above is of the interior of an urban kampong (slums) within Bukit Ho Swee, taken in 1947. Source: National Archives of Singapore, Media Image No: 19980001421 - 0093

Kampong houses were typically made from wood and shared a similar type of roofing – nipa palm roofs, also known as attap roofs. Attap was a readily available material, it had good heat-insulating properties and could protect the inhabitants from rain. The attap would be layered out in sheaves so that it could lift with the breeze and cool the house down.7

Yet, as Prof. Fiona Williamson writes in her article (this section), historic archives highlight how heat waves and dry weather triggered many fire outbreaks. This often turned the wooden houses and attap roofs into potential fire hazards. Intense sunlight and hotter-than-normal heat turned such roofs bone-dry, more brittle, and made them easier to burn. For example, Josephine Chia penned the following memory of a neighbour’s attap roof easily catching fire from a cigarette:8

"One night one of our neighbours, two doors away from our house, was smoking when he fell asleep. The lighted cigarette butt fell onto his pillow and started a fire. His attap-roof rapidly went up in flames. My parents woke us sleepy children and ushered us out of the house hastily. The small passageways or lorongs between the houses made it doubly dangerous as they became packed with people trying to run away from the fire…"

To reduce the risk of fire outbreaks during heat waves, many kampong dwellers doused their attap roofs with water. They also exercised extra caution by extinguishing all flames in their homes, kitchens, and from their joss stick offerings.

Despite these efforts, from the 1950s to 1960s, fire outbreaks were a part of "everyday life" in the kampongs. Lin et al. (2021) compiled a brief history on a string of fire outbreaks during this period:

- 1951: Kampong Bugis

- 1953: Geylang Lorong 3

- 1953: Geylang Lorong 5

- 1955: Kampong Tiong Bahru

- 1958: Kampong Koo Chye

- 1959: "Friday the 13th" fire in Kampong Tiong Bahru

- 1961: Kampong Bukit Ho Swee

There were various environmental and systemic factors underpinning these outbreaks.

The El Niño Southern Oscillation and the Indian Ocean Dipole created prolonged, warmer-than-usual drought conditions in Singapore (and the rest of Southeast Asia).9 Prolonged droughts greatly reduced the availability of water. In the intense heat, kampong dwellers had to prioritise drinking and cooking over the wetting of their attap roofs.

While the colonial authorities started to address fire risk in the city’s commercial and entertainment buildings, they neglected the kampongs. Seng (2009) argues that the colonial authorities were more focused on clearing the kampongs than making them fire-safe.10 One example of fire protection would have been providing kampong dwellers with non-combustible roofs at subsidised prices. Another would have been providing a consistent and sufficient water supply. But neither were pursued.11

In the post-WWII period, the overcrowded urban kampongs were more vulnerable to fire outbreaks. The absence of affordable housing alternatives caused the squatter population to rapidly grow from 127,000 in 1947 to 246,000 in the mid-1950s.12 The density of these settlements increased vis-a-vis their proximity to the city centre.13

Newly-constructed huts followed the pattern of being tightly-packed, with narrow passageways and insufficient fire breaks. Urban kampongs also tended to be situated on hilly ground. The unfavourable geographical terrain coupled with the colonial authorities’ failure to install water mains and telephone lines exacerbated the risk of fire outbreaks.14

The combination of all of these factors meant that a single fire could spread and turn into a settlement-wide fire disaster.

One of the most infamous fire disasters occurred in the Bukit Ho Swee settlement. This disaster helped catalyse massive investment in public housing and the large-scale resettlement of kampong dwellers into modern, high-rise housing units in Singapore.

Image of the 1961 Bukit Ho Swee fire disaster, from Our Home, Oct. 1979. Collection of National Library, Singapore.

Bukit Ho Swee was one of the most crowded attap slums in Singapore, it was filled with thousands of squatter huts and lacked basic sanitary services. On Hari Raya Haji, 25 May 1961, a scorching heat of 32 degrees Celsius caused a fire to break out at 2.50 pm. Emboldened by strong gusts of wind, the fire spread and devoured 19 hectares of squatter homes. Hours later, over 16,000 people from 2,600 families became homeless.15

Then-Prime Minister of Singapore, Lee Kuan Yew, promised that all the fire victims would be resettled in HDB flats within 9 months. By February 1962, the Singapore government and Housing & Development Board (HDB) built the new Bukit Ho Swee Estate on top of the disaster site.

Till today, the Bukit Ho Swee fire occupies a key position in Singapore’s historical narrative, and is frequently cited as an early and definitive moment of progress under the PAP’s leadership. Kwak (2012) reminds us, however, that the PAP’s quick response to the disaster was enabled by decades of housing modernisation programs.16

Nevertheless, the official discourse positions the PAP as rising to an incredible challenge and successfully transforming "one of the unloveliest slum areas'' into a modern housing estate.17 Fire became one strong justification for the rehousing of kampong dwellers into high-rise flats.

Although kampongs were abundant less than 60 years ago, many can hardly imagine living in a community of wooden and attap-covered kampong houses. The shift to modern, high-rise living in Singapore has both reduced the chance of our homes becoming fire hazards but has also removed a key aspect of our landscape and history.

- Xiong, D. X., and I. A. Brownlee. 2018. Memories of traditional food culture in the kampong setting in Singapore. Journal of Ethnic Foods 5, no. 2. pp. 133-139.↩

- NUS Department of Chinese Studies and Department of Geography. 2016. Locating kampongs in Singapore. https://www.nusgis.com/kampongs/↩

- Centre for Liveable Cities. 2015. Built by Singapore: from Slums to a Sustainable Built Environment. Singapore. https://www.clc.gov.sg/docs/default-source/urban-systems-studies/uss-built-by-singapore.pdf.↩

- HDB Annual Report, 1961, p. 9.↩

- HDB Annual Report, 1961, p. 9.↩

- Kleevens, Jan W. Housing and health in a tropical city: A selective study in Singapore, 1964-1967. Royal Van Gorcum BV. 1972.↩

- Ang, K. The Village View: Recalling the Local Farm House. Roots. Last modified 2010. https://www.roots.gov.sg/stories-landing/stories/the-village-view-recalling-the-local-farm-house/story↩

- Chia, Josephine. 2013. Kampong Spirit - Gotong Royong: Life in Potong Pasir, 1955 to 1965. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish International Asia Pte.↩

- Lin, Yolanda C., Feroz Khan, Susanna F. Jenkins, and David Lallemant. 2021. "Filling the Disaster Data Gap: Lessons from Cataloging Singapore’s Past Disasters." International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 12, no. 2, pp. 188-204.↩

- Seng, Loh K. 2009. "Kampong, fire, nation: Towards a social history of postwar Singapore." Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 40, no. 3, pp. 613-643.↩

- Seng, "Kampong, fire, nation", p. 634.↩

- Seng, "Kampong, fire, nation", p. 620.↩

- Kwak, Nancy H. 2012. "The Politics of Singapore’s Fire Narrative." In Flammable Cities: Urban Conflagration and the Making of the Modern World, edited by Greg Bankoff, Uwe Lübken, and Jordan Sand. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.↩

- Seng, "Kampong, fire, nation", p. 634↩

- Seng, Loh K. 2013. Squatters into Citizens: The 1961 Bukit Ho Swee Fire and the Making of Modern Singapore. Singapore: NUS Press.↩

- Kwak, "The Politics of Singapore’s Fire Narrative", p. 297.↩

- Seng, "Squatters into Citizens", p. 245.↩