Alan Choo was only six years old when he picked up the violin for the first time.

The lifelong violinist recalls of his youth, “My dad played the piano, and there was just music in the house all the time.” And when his father saw Alan’s natural ability with the violin, he suggested Alan pursue a career in music.

At that time, Singapore had just established its first conservatory of music through a collaboration between the National University of Singapore (NUS) and the Peabody Institute of The Johns Hopkins University. Founded in 2001 as the Singapore Conservatory of Music, the school was later named the Yong Siew Toh (YST) Conservatory of Music in 2003.

The Conservatory invited musically-inclined students of different ages to apply, so when Alan was in secondary school, he immediately enrolled in YST as part of its fourth batch of students.

It was a life-changing journey that shaped him into the musician he is today, but Alan recalls facing a huge culture shock when he first entered the school.

At only 16, he was the second youngest student in his entire cohort. It was also his first experience meeting so many classmates who came from other countries, many of whom had spent much more time honing their musical skills.

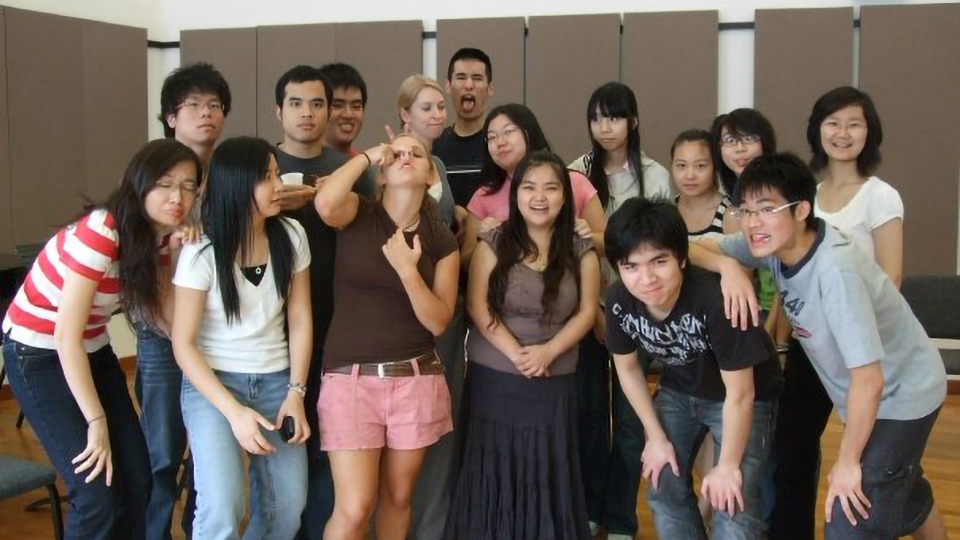

Alan, first row, first from right, with fellow YST students and Conservatory Chamber Singers

Alan, first row, first from right, with fellow YST students and Conservatory Chamber Singers

“I came from a system where academics always ranked number one,” he says with a laugh.

“In the Conservatory, I was surrounded by extremely talented musicians who, since their youth, probably practiced their instruments for eight hours a day!”

Teenage Alan took it as motivation to work even harder on his musical ability, and also to connect with his schoolmates – never mind the age and culture gap.

Over a decade later, he still keeps in touch with and practises with his batchmates. He adds, “One friend is now even teaching in YST and invited me to give a guest lecture at the school the other day!”

That same spirit of perseverance has brought him to where he is on a regular Monday evening amid the COVID-19 pandemic: performing at the Esplanade.

Professionally, Alan is an accomplished soloist and has performed with the likes of the St. Petersburg Symphony Orchestra, Singapore Symphony Orchestra and Singapore Chinese Orchestra. He made his solo debut in 2017 with the Grammy Award-winning Apollo’s Fire Baroque Orchestra, where he continues to serve as an Artistic Leadership Fellow. In 2019, he was also invited to be a guest concertmaster and soloist with the Shanghai Camerata, a Shanghai-based baroque ensemble.

But the founder and artistic director of Red Dot Baroque, Singapore’s first professional period ensemble, counts introducing baroque to the local music scene as his greatest achievement so far.

Baroque, the period in Western classical music history from 1600 to 1750, is characterised by ornate melodies, dance rhythms and driving harmonies. Famous baroque pieces include Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, and Pachelbel’s Canon in D major.

Alan had his first taste of baroque music during an NUS Student Exchange Programme to the Peabody Institute at The Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. While there, Alan met and connected with other musicians, learning many skills and experiencing a multitude of different music styles. But baroque touched him in a way no other musical genre did, and he toyed with the idea of starting a baroque community back in Singapore.

Alan, playing the violin during rehearsal with the St. Petersburg Symphony Orchestra, for a concert which was part of a summer course during his SEP in Baltimore

Alan, playing the violin during rehearsal with the St. Petersburg Symphony Orchestra, for a concert which was part of a summer course during his SEP in Baltimore

“Most Asian countries don’t have baroque ensembles,” Alan adds. When Red Dot Baroque started out, they were the first professional baroque group in Singapore and Southeast Asia to play on period instruments.

While he’s glad to have filled a gap in the local music industry, Alan admits running a successful baroque group is no easy task.

“Starting a group from scratch, and handling the business management side of things – it is a lot of hard work and very stressful, but I wouldn’t have had it any other way.”

Alan (sixth from left) with Red Dot Baroque at Sing'Baroque’s The Seasons of Love concert

Alan (sixth from left) with Red Dot Baroque at Sing'Baroque’s The Seasons of Love concert

at CHIJMES (Photo by Yong Junyi)

Indeed, his efforts pay off when he sees the audience responding positively to the intimate storytelling made possible by baroque. Performed on a smaller stage, this style of music is communicated more directly to the listener and is meant to tell a story.

Explaining the meaning behind one of the most famous Baroque pieces in history, Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, Alan gives an example: “in Autumn, there’s a scene about a drunk man, and the music for this portion reflects this story. So sometimes if the notes are purposefully out of time or even out of tune during those sections, you know why!”

Alan (center) performing with Red Dot Baroque for Vivaldi's Four Seasons at the Esplanade (Photo by Moonrise Studio)

Alan (center) performing with Red Dot Baroque for Vivaldi's Four Seasons at the Esplanade (Photo by Moonrise Studio)

While Alan and his team are brimming with ideas and give their all to their craft, it hasn’t been all smooth sailing for the young group. Like many in the performing arts, they were hit hard by COVID-19. Initially looking forward to touring the United States in June 2020, travel restrictions meant that all their efforts planning for it eventually came to naught.

However, the group picked themselves up and chose to make the most of a disappointing year. “We pivoted and spent the time filming music videos, films and concerts instead,” Alan says with pride.

The ensemble recorded a total of five music videos, all filmed and produced locally. They also recorded short concerts, which aired online at digital art festivals. “2020 ended up being a hugely fulfilling and productive year,” Alan declares.

Just recently, Red Dot Baroque embarked on a new venture: being the ensemble-in-residence at Alan’s alma mater.

Returning to his stomping ground after graduating a decade ago, Alan is excited by the changes he has observed.

“Even back then, I saw the Conservatory as an emblem of high musical accomplishment and talent. It was a pool of all the best music students in Singapore. One thing that I see has changed is how much the school has grown, and how students are getting a more holistic education and are exposed to more ideas!”

As an ensemble-in-residence, Red Dot Baroque has a hand in shaping the future of the Conservatory’s students. “We’ve met with interested students to advise them on their music career, and even talked shop about the organisational, executive side of running an ensemble.” Alan says.

“My favourite thing about the residency is being able to open the eyes of so many new talents to the spirit of baroque music.”

The group will also get to perform one concert a year at the Conservatory. “YST has helped our group immensely in the past. As a baroque ensemble, we have to rehearse in special locations with access to unique instruments that are stored in a temperature-controlled room. The school has always supported us by offering us rehearsal space. This residency is a good way for us to give back.” he says.

“It feels great to be able to share insights with the students,” Alan says. “It’s a good way to contribute to the growing level of musicians in Singapore, since YST is so central to this industry.”

As a lifelong musician, Alan’s advice to prospective students is simple. “Be okay with not knowing what you want to do yet,” he says. “It takes a lot of time to find your identity as an artist.” He adds that one should be as open-minded as possible, and consider other artforms, cultures, and ways of expressing music when discovering themselves.

Additionally, being a good musician is more than just how well one plays their instrument.

“When I was a student, my peers at YST were playing at a super high level - the skills they had on their instruments were just amazing,” Alan recalls. “But I realised, that’s just a small part of being a successful musician.”

Having founded his own ensemble, Alan knows first-hand that soft skills are equally important, such as creating synergy in a team, organising shows and marketing.

In his view, keeping an open mind might be the best quality a musician can have. For example, instead of approaching music with a one-track mind, local musicians can explore collaborating with non-music art forms, and ways to launch their ideas into the future.

“It’s nice to see how music can break boundaries, from language barriers to digital barriers, and link people of different cultures even more closely together.”