From Acedia to Choice

The COVID-19 pandemic has changed everything, and yet it has changed nothing, say Dr Adrian W. J. Kuah and Ms Katrina Tan (Arts and Social Sciences ’98).

Dr Adrian W. J. Kuah

Director of the Futures Office, NUS.

Ms Katrina Tan

Associate Director of the Futures Office, NUS.

As part of our COVID-19 containment strategy, we in Singapore hunkered down the way the English ‘plague village’ of Eyam did in 1665-1666 (when combatting the Black Death) — by closing borders, self-isolating, socially distancing, and meeting outdoors only when really necessary (i.e. church, in the case of the villagers).

Other than that, life in our present day continued pretty much as it always did. We turned up and showed our faces/avatars on Zoom, performed while being watched, and produced as much as — if not more than — we did in the old normal. Essentially, we transported what we did at school or the workplace to the home, and put it on steroids. In her 2021 paper “The Inappropriable: On Oikology, Care and Writing Life”, Kélina Gotman calls this “perpetual performativity… constant presenteeism, hyperproductivity, and hypertrophic mechanisms of surveillance and control.” In spite of, or maybe due to, the maintenance of this semblance of normality in a clearly abnormal situation, global levels of stress have skyrocketed.

The United Nations has said that mental health and the wellbeing of whole societies have been severely impacted, and that psychological distress is widespread. Unless some action is taken, we are on the brink of a major mental health crisis. The journal

Nature reported on this uptick, and highlighted that the young (in particular women), those with young children, and people with a previously diagnosed psychiatric disorder, are most vulnerable.

However, as a 1999 study by Joseph Volpicelli on the role of uncontrollable trauma in the development of PTSD points out, it is not uncommon for people to experience a traumatic event — and experiencing one does not necessarily lead to psychopathology. He cites other studies which place the proportion at eight per cent of the population who suffer prolonged consequences from trauma. This is supported by

The Lancet’s COVID-19 Commission Mental Health Task Force, which stated that most people should be able to return to pre-pandemic routines without impact on their mental health.

It may, therefore, be rather gauche to declare that everyone has some form of mental illness and needs to take care of it. But what if the pandemic has irrevocably changed us, without making us mentally ill? In the words of Danish poet Naja Marie Aidt:

![]()

But what happens when an event occurs that is so catastrophic that you just change? You change from the known person to an unknown person. So that when you look at yourself in the mirror, you recognise the person that you were, but the person inside the skin is a different person.

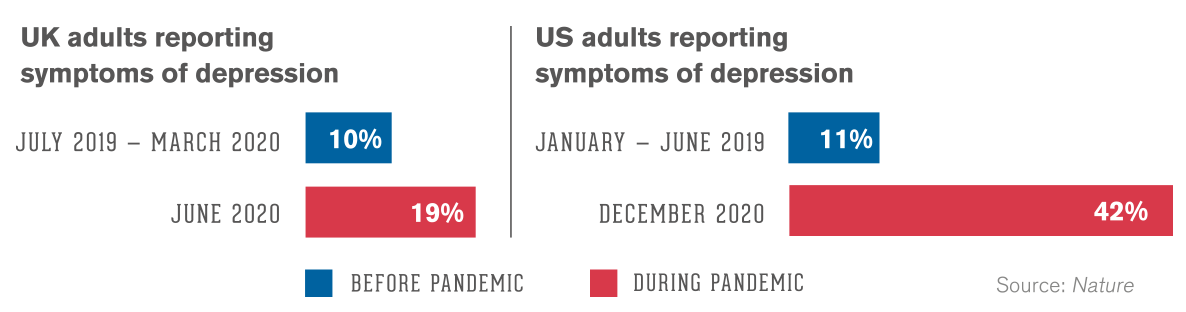

COVID-19 mental stress

The percentage of people experiencing symptoms of depression and anxiety has surged amid the COVID-19 pandemic, data from nationally representative surveys shows.

As we move into a future where COVID-19 is endemic, what if we have changed so much that we can’t, or won’t, go back to the past ways of living?

Can’t or Won’t?

As the pandemic extends into its second year, the pressure to kickstart the economy and get back to normal becomes ever more urgent. People are being pressed to return to the state of ‘before’. But what if people refuse to, for various reasons? What if, as Aidt points out, we are now a “different person”? Maybe one who has become so inured to this lack of purpose, that a numbness has set in? Or that the pursuit of previously sought-after material wealth and social status no longer holds meaning? What if people have adapted so much to the new way of life that they are willing to relinquish certain benefits so they can continue with what they have now? What if the experience of the pandemic has caused uncontrollable trauma, such that people simply cannot return, and need to hunker in place?

![]()

The United Nations has said that mental health and the wellbeing of whole societies have been severely impacted, and that psychological distress is widespread. Unless some action is taken, we are on the brink of a major mental health crisis.

Acedia / Sian / Languishing

Some authors have suggested that following the initial panic and grief in 2020, we have collapsed into ‘languishing’ in 2021. One definition of languishing is “a sense of stagnation and emptiness,” while another is the vague lack of purpose, sometimes while beavering away at work.

Two recently-created neologisms — 内卷 (nèijuǎn) or ‘involution’ (a novel definition by 985 Waste), and 躺平 (tǎngpíng) or ‘lie flat’ — have caught the attention of young Chinese and the government. While nèijuǎn conjures images of a hamster running madly and getting nowhere on a hamster wheel, tǎngpíng is the solution to that mindlessness — stepping off the wheel. Both are responses to the doomed project of self-advancement and fulfilment of society’s expectations, with no possibility of reward. Whether this was caused or accelerated by COVID-19, a protest against the unfair expectations of the 9-9-6 Chinese work culture, an ideological emancipation from consumerism, resistance against the constant need to be socially responsible, or people simply being defeatist or stoic, is irrelevant. As the originator of tǎngpíng, Kind-Hearted Traveller, points out, the phenomenon has enhanced his physical and mental freedom. This is, therefore, the individual wresting back control in an uncertain and uncontrollable time. It is the choice to settle for enough, rather than strive for the unattainable.

And yet, this phenomenon is not necessarily new. Downshifting, or the voluntary choice by individuals to change aspects of their lives in order to create a simpler lifestyle, has been on the rise in the UK and the US for several decades. This downshifting is in line with the Aristotelian concept of oikonomy, whose goal is for health, virtue, and human and communal flourishing, within the community. It is the antithesis of chrematistics, or the art of acquisition, i.e. profit maximisation, the neoliberal order and the rat race. Gotman speaks of the shutdowns allowing the emergence of a new paradigm, an oikonomy of care. Her incomplete Manifesto for an Economy of Care states:

- The current pandemic is not a matter of virology only, but an entire social, political and economic system that is falling apart. What the virus shows is that we do not have enough support for the vulnerable; that all of this support structure has been cut.

- It is not merely sufficient to shore up national healthcare systems, but necessary to entirely rethink the way we live our social, political and economic lives. This means that health has to be understood as the bedrock of our lives, and not as something that can be tacked on after.

- We mean by ‘health’ not just the vitality of the neurobiological system, but an entire system of emotion and affect as well: anxiety and fear are all part of the ‘health’ systems of our lives. They affect our immunity and ability to thrive.

- ‘Work’ has been taken as central to the economic productivity — the productivism — of the capitalist paradigm, at the expense of ‘private’ life. We are calling for a shift towards an economic culture that protects the family home, however it may be construed: of same sex, opposite sex, multi-generational, single, or whatever sort.

- ‘Private’ life is vital and necessary for allowing thoughtful, caring life.

And yet, just as many young Chinese will continue to “roll”, Gotman admits that she will continue to perform and conform, because lying down offers no connections and no sense of security and freedom from want.

But maybe, this is the opportune time for us to reconsider whether there truly is a need for the relentless pursuit of chrematistics, and whether and how we can downshift from the 9-9-6 work culture.

Taking back control

As the pandemic settles into a predictable normalcy, more companies have been calling staff who have been working remotely for more than a year to return to the office. Schools are opening and calling students back for face-to-face lessons. In the workplace, distinct camps have cropped up. One camp is willing to relinquish benefits, forgo a US$30,000-a-year raise and even quit in order to choose where they need to work. The other has those willing to pay to come into the office.

While it is still early days, the hybrid model of working both at home and in some specified location has gained traction. What this specified location is, however, could be different for different people, situations and companies.

The pandemic has changed the way we view the spaces we exist in. The conjoining of our first (home) and second (workplace/school) places, as Ray Oldenburg (1989) posits in The Great Good Place, was traumatic for many. However, the long adjustment has allowed some to create a “fourth place” (Morisson, 2018). This is a space where previously clear boundaries between work, home and the third place (shared, community spaces like parks and coffee shops), as Oldenburg highlights, are blurred to create a place that generates interaction, stimulates mingling, cooperation and frontal communications, and supports the exchange of implied knowledge. This place exists outside a singular physical space, and instead is any space where these activities can occur. The hybrid model of work not only brings back the sacred delineations between the first and second places; it gives people agency to convert these places, along with the third place (even Starbucks is redefining their concept of this), into the fourth, where and when desired. Similar to the tǎngpíng phenomenon, it returns control to the individual.

Key Findings

Key Findings

64% of employees would pay out of their own pocket for access to office space.

79% of the C-suite plan to let their employees split their time between corporate offices and remote working, if their job allows for it.

1 out of 2 employees would prefer to spend 3 days a week or fewer in the office, and when they do go in, they want to be there 5 hours a day or less.

75% of employees would give up at least one workplace benefit or perk for the freedom to choose their work environment.

76% of the C-suite say they are likely to give their staff a stipend to work from home or a co-working space.

2X After COVID-19, employees who are more satisfied and engaged want to spend twice as much time in locations other than their home or corporate office than less-engaged colleagues.

Source: WeWork

COVID-19 is dead, long live COVID-19

In his model of epidemic psychology, Philip Strong (1990) says that alongside the medical footprint, we must take heed of the epidemic of fear, which includes irrationality, fear, suspicion and stigmatisation. Strong refers to these when he points out how 600 years on, the Black Death still has extraordinary historical resonance in popular culture, despite it becoming “normalised and institutionalised” in later years. In a word, endemic.

The Ministers in charge of the COVID-19 Taskforce speak of a time when COVID-19 becomes endemic, and we can “get on with our lives”. Some researchers have suggested flipping this switch may not be so easy. A 2020 study by the Anxiety & Depression Association of America shows that 17 years after recovery, SARS patients and their relatives, as well as those placed in quarantine, showed signs of PTSD and other psychological issues. A study on the manifestation of physical and mental ailments post-9/11 shows similar results. Correspondingly, a 2018 replication study in the Community Mental Health Journal also suggests that while the general public eventually returns to a normal pre-adversity level of functioning, this may not be due to distress symptoms disappearing, but because people have better recovery and coping strategies.

To enable this recovery and mitigate this epidemic of fear, the language used in dealing with COVID-19 needs to change. From the outset, many national leaders invoked the language of war, as seen in references made to World War II in articles by McKinsey and BBC Future. Daily death toll reports, disruption of normal life routines, shortages of certain services, conversion of industries and global economic decline were par for the course. And yet, the COVID-19 pandemic is not a war. We are not fighting an enemy who wants to kill us especially for specific reasons. We do not need to hate the enemy, nor be ever-vigilant — remember “Loose lips sink ships”?

Commentators have cautioned that while the war metaphor calls for solidarity and national cohesion, it is also divisive. It drives antisocial behaviours like racism and xenophobia, and fuels anxiety and panic. We have seen this in the global obsession with toilet paper, price gouging on masks and hand sanitisers, and the many trending topics that perpetuate ethnic and racial discrimination. Furthermore, the actions this war demands in forced lockdowns, closures of schools and businesses, and postponements of major personal, national and international events, have created deep uncertainty, and stripped many of any sense of control. All these reinforce the epidemic of fear.

Some leaders have tried to change the rhetoric. Danish Queen Margrethe II has called the virus “a dangerous guest”. This is a fascinatingly apt metaphor, as like a guest, we invited the virus into our house, and now have to patiently await its timely departure. The Director General of the World Health Organization, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, has used a sporting metaphor, “You can’t win a football game only by defending. You have to attack as well.”

As we try to entice people out of their homes by showing it is safe to come out, governments need to moderate their language and change the tone of their efforts. War metaphors are used to impress the seriousness of the situation on people. We are past that. We need a language of togetherness and care to move into the next stage. An oikonomy of care, if you will. As pointed out by Rutger Bregman (2020) in Humankind: A Hopeful History, humans are hotwired to seek out the exceptional and dramatic, the ghastlier the better. As ghastly as this pandemic has been, it has given us time to take stock of what matters and consider what we value. We are at the edge of the woods and can choose which road to take.

Will we take one less travelled?