1 April 2025

CAPTURING THE WEIGHT OF THE UNSPOKEN

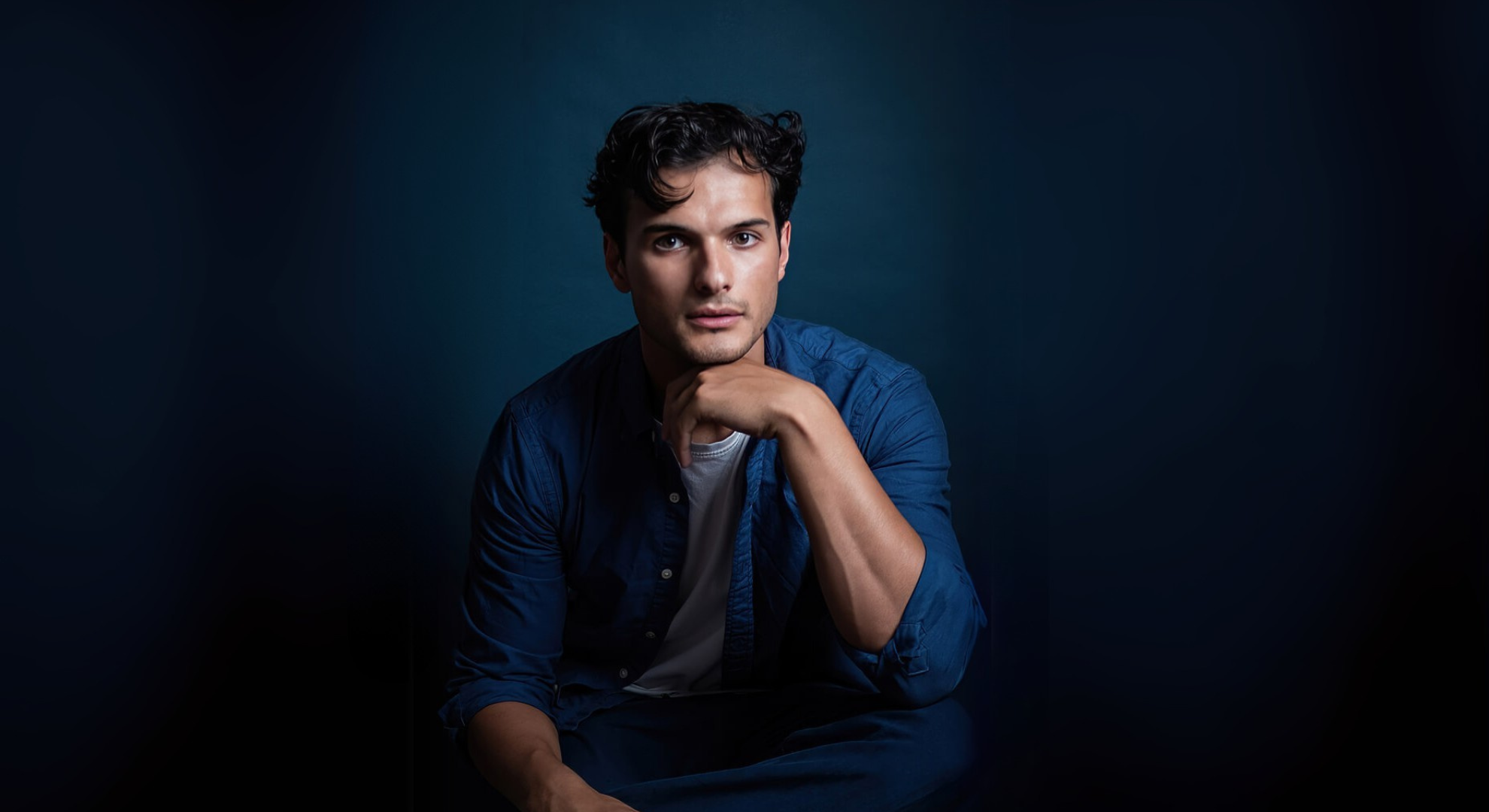

Shaped by faith, loss and wanderlust, the work of author Mr Raeden Richardson (Yale-NUS ’17) searches for meaning in grief and myth.

Mr Raeden Richardson

WHO HE IS:

Mr Raeden Richardson is an Australian writer. His debut novel, The Degenerates, is a bold exploration of grief, memory and the limits of language. Shaped by his time at Yale-NUS College, his narratives traverse continents and decades, probing fractures of the human condition. A graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, his work has been featured in The Sydney Morning Herald, Griffith Review, Australian literary magazine Kill Your Darlings and New Australian Fiction.

For Mr Raeden Richardson, writing is more than an act of creation — it is one of preservation, an attempt to capture the weight of memory, navigate loss and make sense of the ineffable. His debut novel, The Degenerates, is a raw and unflinching portrayal of grief, longing and human frailty, influenced by his encounters with silence and the struggle to articulate what often resists language.

Born and raised in Melbourne, Mr Richardson remembers a childhood filled with unstructured freedom. “I grew up in the outer suburbs of southeastern Melbourne, in a place called Waverley Park,” he said. “In the early 2000s, there were lots of big housing developments just getting started — empty lots, vast open spaces that seemed to fill up my mind.” He and his friends roamed freely, sneaking into unfinished construction sites. “We would make up stories and write them, often about serial killers on the loose and this strange wasteland we lived in,” he recalled with a laugh.

His Catholic upbringing also shaped his storytelling. “I was constantly in church, and I wanted to be an altar boy. I was quite devout,” he said. Immersed in biblical stories, he was drawn to the grandeur of Christ’s miracles and the moral struggles of his followers. As Mr Richardson grew older, his engagement with faith evolved, but the imprint of those narratives remained. “I started thinking about how stories record and make sense of suffering, the passing of time, and the possibilities of myth, art and writing as a way to acknowledge — and maybe redeem — the suffering of a life.”

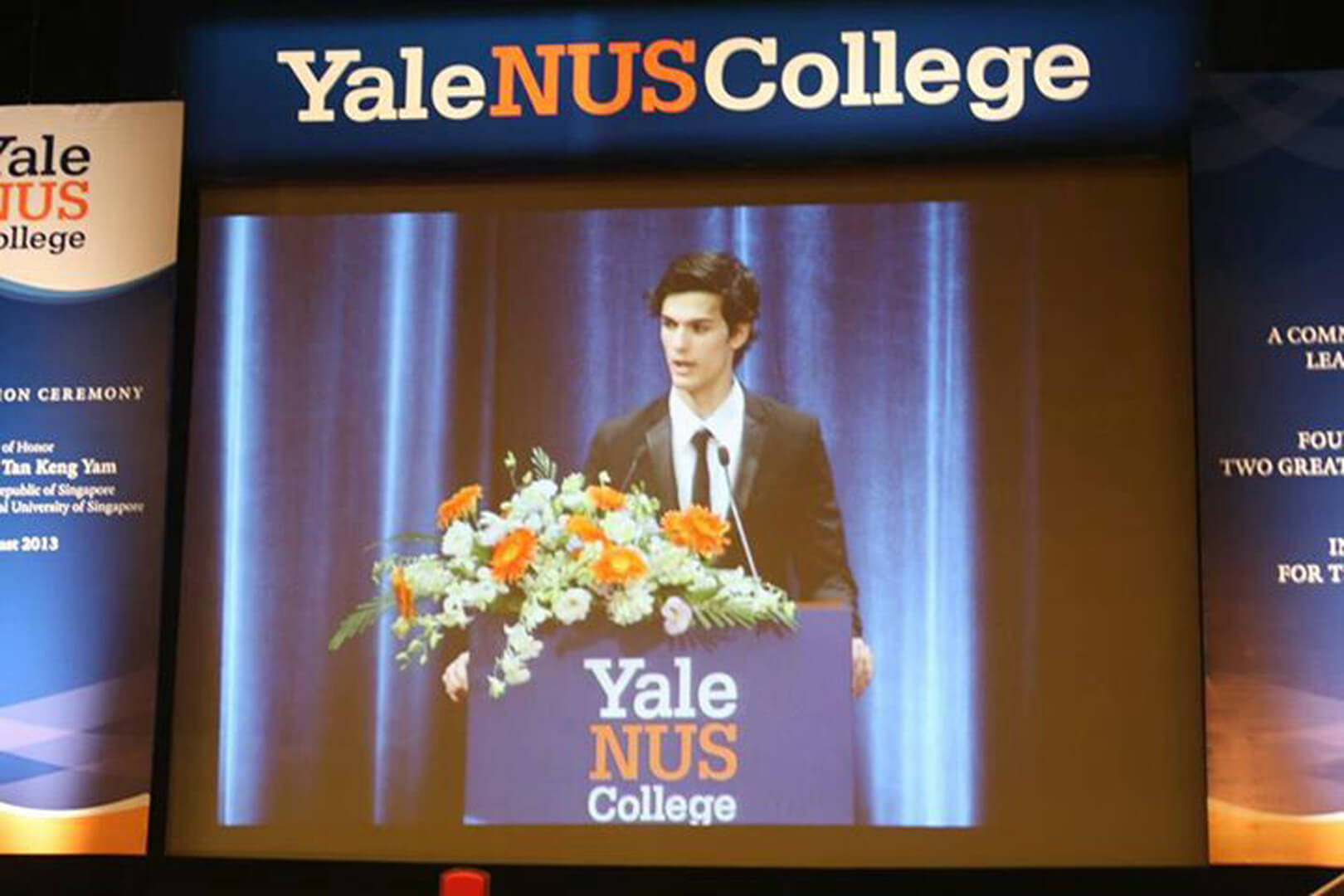

Mr Richardson at the Yale-NUS inauguration in 2013

A STORYTELLER'S GLOBAL CANVAS

His journey took a decisive turn when he attended Yale-NUS College in Singapore — his first time leaving Australia. Yale-NUS provided an intimate learning environment, one that dismantled traditional academic hierarchies and encouraged students to engage with a truly global intellectual landscape. “Going to Singapore and being a part of Yale-NUS was this incredible opportunity to be uprooted and, at the same time, to be welcomed into a new place,” he said. “It provided me a chance to engage with thinkers, philosophers, writers and artists from around the world.”

During this period, he also faced one of the most difficult moments of his life — the suicide of a friend. “It was my first encounter with loss like that,” he said. “I remember distinctly this tremendous silence that fell across my classmates and within myself, realising that this tool I’d been developing — writing, articulation, specificity — was blunt when it came to things like this in life. It renders your language useless.” That silence stayed with him, becoming a question that would shape The Degenerates: What happens when language fails?

The cover of The Degenerates

The cover of The Degenerates

The novel — which took seven years to complete — is a sprawling, multi-layered narrative of grief, addiction and memory, moving between Melbourne, Mumbai in the 1970s and New York in 2016. These settings are integral to the novel’s structure, reflecting the characters’ fractured journeys through time and place. It has been compared to Irvine Welsh’s cult classic Trainspotting for its visceral, lyrical intensity, weaving together the grotesque and transcendent.

Reflecting on one of the novel’s key settings, Mr Richardson noted: “One of the beautiful things about Melbourne, if I might be so audacious to say, is that it has this quality of celebrating the battler, the degenerate or the little guy who is flawed in some way. That’s the spirit of the book too — centring these figures one might not necessarily want to be friends with.”

Some readers have found the flawed nature of his characters unsettling. “I had a friend who was quite troubled by how unlikeable they all were. They do such bad things, they steal things, they lie, they get into trouble.” But that was the point, said Mr Richardson. “These characters might drive you crazy. But they are still worth holding on to, even if they are ruinous in some way.”

THE ROAD TO ACCLAIM

Despite his belief in the work, publication was uncertain. “Although I loved the book dearly and believed in its integrity, I didn’t think it would ever be published because I felt like it was too out there, too much, too unruly,” he said.

Even when it finally found a home with Australian publisher Text Publishing, seeing it in print was surreal. “For years, the book existed in different forms — handwritten notes in a journal, then typed up, double-spaced in a Word document, then a PDF I printed out,” he recalled. “But I had never actually held it in two hands as a printed book, flipping through the pages side by side. That was the fullest expression of it, the endpoint of the book, but it still felt strange — like I was looking at it from the outside.”

Since its release, The Degenerates has received critical acclaim. The Guardian called it an “ambitious debut that pulses with life and language”, while Liminal Magazine described it as “brimming with vitality, humour, intelligence and brilliant writing”. Now, Mr Richardson is already immersed in his next novel, an ambitious historical work set in first-century Rome and Judea.

Mr Richardson (right) with poet Lawrence Ypil at a Yale-NUS event

Mr Richardson (right) with poet Lawrence Ypil at a Yale-NUS event

Mr Richardson presenting to students at Melbourne High School

Mr Richardson presenting to students at Melbourne High School

FUTURE OF STORYTELLING

His advice for aspiring writers is to practise equanimity. “You’ll write something one day and feel like it’s the most wondrous, exciting, provocative and enchanting thing in the world,” he said. “And the next day, you’ll read the same thing and think it’s so boring, derivative and useless that it should just be thrown out.” He encouraged young writers to resist the pressure to rush. “Being able to shift your relationship with time is very important. You have to slow down. Letting the work develop and cultivate is crucial.”

Looking ahead, Mr Richardson sees exciting challenges for literature in a rapidly evolving world. “The pressures of artificial intelligence and the ways in which it can, in some ways, imitate conventional storytelling are important,” he said. “It’s exciting because artists and writers will have to shift and constantly be thinking about what makes a human novel distinct from an artificial one.”

Beyond the craft, literature itself serves a deeper purpose. “One of the most exciting things is that people from radically different cultures can come together through their stories,” he said. “It reminds us how tremendously connected the world is.”