Social Studies

Artist duo Chow and Lin – Mr Stefen Chow (Engineering ’03) and Ms Lin Huiyi

(Arts and Social Sciences ’03) – marry their abilities to draw attention to global issues.

She is the bookish-looking Senior Director for an agricultural and animal health marketing consultancy; he is the globe-trotting photographer and film director with a perpetual five o’clock shadow. She speaks the language of numbers; he, that of images. They might seem like chalk and cheese, but together, married couple Ms Lin Huiyi, 38, and Mr Stefen Chow, 39, have forged a unique expression that has captured the world’s attention.

Their seminal work

The Poverty Line appears to the untrained eye as a series of food items from different places around the world, shot on a background of a local broadsheet. Two banana blossoms from Phnom Penh. Five strawberries bought in Beijing. Thirty portions of dried pasta purchased in Geneva. Yet, a picture paints a thousand words. Created on the foundation of hard data on poverty as defined within each country, each image depicts what those living on the poverty line in the respective territories can afford for food each day. The photographs might not stir your emotions like that of a portrait of a starving child. In fact, they are not tinted with emotion, simply directed by the data gathered through research. Yet, they are powerful expressions that provoke thought about social issues, and inspire self-reflection.

The project, which started in 2010 and took eight years to complete, was referenced by the World Bank and exhibited around the world, including at Pavillon Carré de Baudouin in Paris and PMQ in Hong Kong. It is currently in the permanent collection of Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Photography, and Beijing’s Central Academy of Fine Art Museum. Since then, the couple has embarked on three more projects, with their latest installation

Homeless on display at the NUS Museum until 27 April. “We honestly didn’t (foresee our work having such a global impact),” shares the Beijing-based duo in an email interview. “When we started on our first collaborative project nearly ten years ago, it was more of a one-off thing. We didn’t expect the huge response that came with it, and felt that perhaps there is something to this.” They thus went on to self-fund further projects: “This is bigger than the sum of the two of us.”

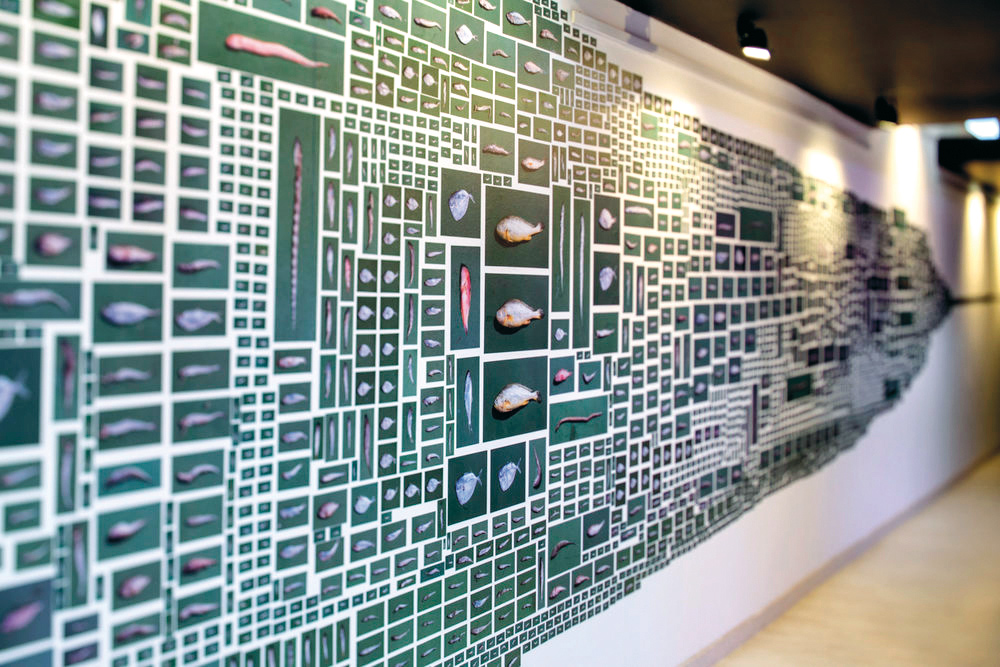

The Fish Equivalence on display at the Getxo Photo Festival in Spain in 2018.

The Fish Equivalence on display at the Getxo Photo Festival in Spain in 2018.

How are the topics for your works decided upon?

Stefen Chow (SC) & Lin Huiyi (LHY): We are concerned with global tipping points, and these are all human-inflicted conditions. The topics range from poverty, consumption and forced migration to inequality. Our first project, The Poverty Line, started in 2010 because it was the topic closest to our hearts. Incidentally, both of us were born into rather well-to-do families, only for our fathers to lose everything in business before we were old enough to go to school. We had discussed this project ever since we started dating in our freshman year in NUS. Other topics were also explored, and they sometimes pop up in our conversations with other academics, some of whom have become good friends. We keep an open and inquisitive mind, as we don’t see ourselves as experts in these fields, but rather as an artist duo with an interest in issues that affect our current generation and the future.

Please illustrate your work process, citing an example.

SC & LHY: Our work takes a closer look at issues, to unearth truths that are out there but often overlooked. We start by asking experts in the topic lots of questions to uncover facts. For Equivalence - Fish, we worked with scientists and fish experts along with Greenpeace to look at the environmental impact of what we eat. The yellow croaker is China’s most widely-consumed fish, but is severely overfished. It is farmed today, and sold in markets, which seems like a good thing to the consumer – the prices don’t fluctuate wildly, and the supply is available all year round. However, we realised that the same fishermen who used to catch the yellow croaker now resort to catching smaller fish and by-catch, which is used to feed the farmed fish. Their nets have become more tightly knit to catch these smaller fish, and they end up hauling fish indiscriminately and in excessive volumes. This creates a catastrophic effect on the marine ecosystem. To illustrate our findings, we created a visual map of the food chain: a 14m x 2m installation that shows the sheer amount of small fish it ‘costs’ to raise a 1kg farmed yellow croaker.

What role do each of you play in the process?

SC & LHY: Lin is the brains, while Chow is the eyes and the mouthpiece. It helps that we were in a relationship before we had any inkling to be artists, and we communicate deeply and freely about everything. We influence each other, and there are overlaps in our roles. That is the beauty of Chow and Lin – it is the combination of us both, and these works wouldn’t be possible with the absence of either one.

Do tell us about your current exhibit at NUS Museum.

We keep an open and inquisitive mind, as we don’t see ourselves as experts in these fields, but rather as an artist duo with an innate interest in issues that affect our current generation and the future.

SC & LHY: We were approached by NUS Museum’s curatorial department two years ago to discuss how we could plan for an exhibition together. The project probes into Big Data that reduces individuals and societies into data points by problematising issues in society. As we researched the topic, we came to realise that global inequality and the refugee crisis are at unprecedented levels. Privacy issues have also been exposed through social media, and we see the world tipping off its balance. Our hope is that more people can see our work and have rigorous conversations about it. Some professors have arranged modules and tutorials around our projects, and we are very excited about it.

Who are the people who shaped you into who you are today?

LHY: My parents. From my father, the concept of “饮水思源”, which is a drive to contribute to society and remember my roots. From my mother, the courage to face challenges and do my best.

SC: My father, who taught me what it is to fall again and again only to pick yourself up. I witnessed it myself growing up, and he brings with him a sense of humility and openness that I admire till this day.

Stefen, you summited Mount Everest in 2005, as part of an NUS team. How did that impact you?

SC: Climbing Everest with the NUS Centennial Team remains a cornerstone to my life. It convinced me that hard work – and having Lady Luck on your side – allows you to fulfil impossible dreams. I learnt this when I was 25, and it still guides me in my life and work.

What values do you wish to pass on to your two children?

LHY: Treating others with respect and empathy, speaking up for what is right, and believing that each one of us can be an agent for change. I try to use actual life incidents to explain our values and how they define who we are and want to be.

How would you define a life well-lived?

LHY: To have created a positive impact on society, built relationships based on love and respect, and grown to be a more “complete” person.

SC: To look back and realise that your dreams have become your reality, that you don’t regret much in life. If you have laughed more than you cried, you are doing okay.

Text by Koh Yuen Lin