Moving Pictures

The Virtual Wallace Collection is now available online, visually illustrating the most complete record of Singapore’s natural history heritage from the 19th century.

Imagine Singapore in the early 19th century. In the wake of the Singapore Bicentennial, plenty of people did exactly that this year, speculating what life was like at the time of Sir Stamford Raffles’ arrival, with others then going as far back as 1299, when the Kingdom of Singapura was founded. Several commemorative exhibitions and events held this year have done much to fire their imaginations. But these narratives are by and large, the story of people, and of culture. While colourful and dramatic, they often ignore a crucial element…

“The Singapore Bicentennial is not only about human heritage but also natural heritage,” says Professor Rudolf Meier from the NUS Department of Biological Science. “We have only very incomplete knowledge of which species lived in Singapore in the 19th century, but this is also part of the country’s heritage.” Prof Meier knows a thing or two about this, because he and his team — including Research Fellows Dr Ang Yuchen (Science ’08) and Dr Wan F A Jusoh — happen to be part of an effort to build a virtual collection of Alfred Russel Wallace’s collection of specimens, collected in the middle of the 19th century in Singapore. A contemporary, and some say rival, of the great Charles Darwin (see box), Wallace conducted what could be called the first recorded survey of Singapore’s biodiversity, but the results have always been a bit of a mystery because the specimens from Singapore were sold to European collectors. Prof Meier and team embarked on their quest to shed light on this mystery.

Dr Wan F A Jusoh. Dr Ang Yuchen and Professor Rudolf Meier with a specimen of a cerambycid beetle, an example of an insect that is part of the region’s ecosystem.

Dr Wan F A Jusoh. Dr Ang Yuchen and Professor Rudolf Meier with a specimen of a cerambycid beetle, an example of an insect that is part of the region’s ecosystem.

From here to London, and Back Again

In many ways, the story begins in 1854, when Wallace dropped anchor in Singapore. Over the next eight years, he surveyed the biodiversity of this part of Southeast Asia, and used Singapore as a base for his expeditions. He visited Singapore four times and used his 222 days on the island to collect fauna samples.

Most of the material is now in the Natural History Museum (London) where the specimens are dispersed throughout the collections. Because the specimens are dispersed, we do not know precisely what species Wallace collected. This is why the results of the earliest and most extensive biodiversity survey of Singapore from the 19th century remain incompletely known. Researchers Dr Ang and Dr Wan went to work on completing the survey, spending three and four months respectively at the museum meticulously recording everything — including all the information on the original labels — and photographing the specimens. To give you an idea of how painstaking this process was, it took an average of 25 minutes to photograph every specimen, meaning both researchers worked from dawn to dusk every day. On occasion, the museum staff would come and shoo them away at closing time.

Sparking Curiosity

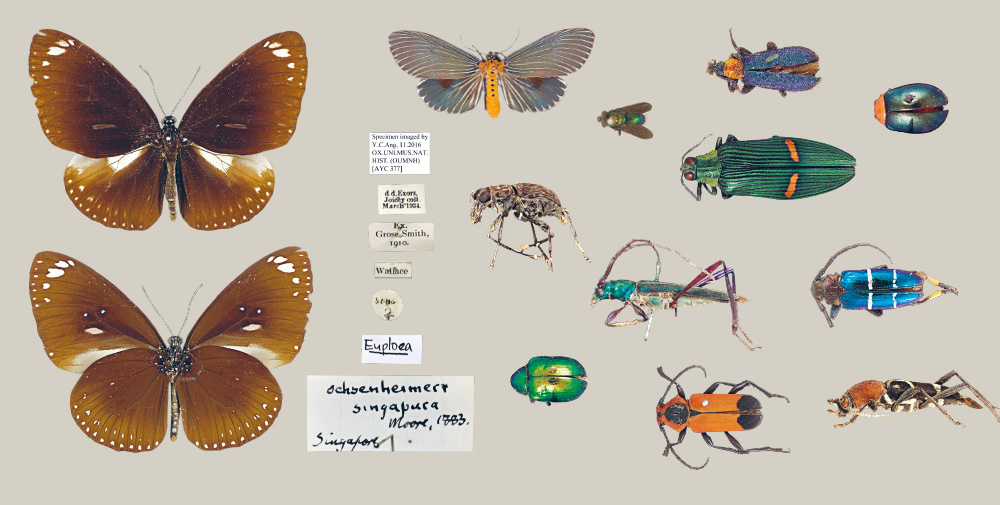

The results of these photographic sessions can be viewed at wallace.biodiversity.online. “My hope is that someone will look at the pictures of insects and discover all the marvelous structures on their bodies,” says Prof Meier. “Then they will go and investigate further. This is how you build appreciation, via visual stimulation. It’s about sparking curiosity.”

The pictures are truly stunning, and they highlight a treasure trove of information, since each image is tied to the notes Wallace and company made. This library represents a virtual repatriation of the Wallace specimens, since these are mostly too fragile to transport from the UK. This digital archive now adds immeasurably to the modest collection of actual Wallace specimens at the Lee Kong Chian Museum of Natural History.

It will also become evident, looking through the Virtual Wallace Collection, that Wallace collected plenty of bird and insect specimens. Prof Meier and the team think it is worth taking a moment to realise the importance of insects – and other less-photogenic elements of the biosphere – in the record of biodiversity, and in its future. “When it comes to keeping (the world) going, if you only have birds, butterflies and trees, the forests will be dead in 10 years,” says Prof Meier. “You are missing the bigger picture. You have to have (fungi) to recycle decomposed organisms into nutrients, and insects to do the pollination, and control pests. Basically, if you kill off all insects, life comes to an end.” Indeed, scan through the images and you will find specimens that are listed as ‘Nationally Extinct,’ and the chances are it is an insect specimen. Overall, this highlights that we already know that things have changed in the 21st century.”

Towards a New Survey

There are three steps in this current project that Prof Meier’s team is running, only one of which is the building of the Collection. The team has located the relevant specimens and recorded them, and now can use the information to build a baseline to carry out a repeat survey to capture the state of Singapore’s current biodiversity. “Few countries have gone into the historical record of biodiversity. What we have found (the fruition of the current project) establishes a baseline for doing that,” says Prof Meier.

Basically, Prof Meier and the team are undertaking a new survey to identify conservation priorities in Singapore. The idea here is pretty easy to understand: with the background and understanding of the Wallace survey, a new survey may reveal how things have changed, uncovering how much of Singapore’s biodiversity is intact. “Here Singapore has an advantage, not only because it is small, but because…Europe’s original forests were lost thousands of years ago,” says Prof Meier. “Even though there were disturbances in the 19th century (in what is today Singapore), biodiversity was still present and was probably closer to the natural state than you would get if you compared European biodiversity today with that of the 17th century, for example. Deforestation and such here took place while scientists were already collecting samples.”

A new survey would of course look for the presence of the same species Wallace found, obtain genetic samples and DNA barcodes for all species for future monitoring through environmental genotyping, and of course to photograph all new species. The implication here is that the new survey will be a thoroughly modern project; the team tells us that Wallace and company would have been armed with rifles to shoot the animals, which they would then preserve. Obviously, field researchers no longer need to resort to these tactics!

What will such a current survey find? Hopefully an example of something like the cerambycid beetle the team is pictured with here. Otherwise known as Batocera thomsoni, it is not uncommon in this region, and is recorded in the Wallace Collection too.

ABOUT ALFRED WALLACE

One might recall Alfred Russel Wallace (1823-1913) as the co-discoverer of the theory of evolution by natural selection; he is remembered today for lending his name to the Wallace Line, which divides the fauna of Asia from that of Australasia. He also published

The Malay Archipelago, a book recounting his scientific adventures in this region. Wallace was one of the first prominent scientists to express concerns over the environmental impact of human activities.

A recently-unveiled statue at the Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum at NUS commemorates the contributions of Alfred Russel Wallace and his assistant Ali to the understanding of Southeast Asia’s ecology.

Text by Ashok Soman. Group photo by Wilson Pang.