Where Do We Draw The Line?

In this special commentary, NUS Health and Wellbeing Team examines the impact of sexual objectification on social media.

Have you ever been catcalled or wolf-whistled at from across the road? What about being soundlessly looked over from head to toe the moment you step into the office by a co-worker? Has an acquaintance or relative ever made remarks about your dressing, weight or looks?

You are not alone.

Most people would have experienced it at least once, at some point. This may seem relatively innocent to some, with others brushing it off as the recipient being “too sensitive” or that “it was just a joke”. But is it? Where do we draw the line between what is a joke and what is not? The truth is that such incidents classify as sexual objectifications. Sexual objectification can happen to all genders, offline or online. Women are more frequently targeted, both actively and passively, especially on social media platforms.

sexual objectification: what it is, and where it comes from

‘Sexual objectification’ refers to the process of reducing women to objects whose worth is based on physical and sexual attractiveness such that their personality, abilities and individuality are devalued. This means that women are valued for their physical appearances rather than who they are or what they can do. This process has been linked with sexual aggression and violence against women.

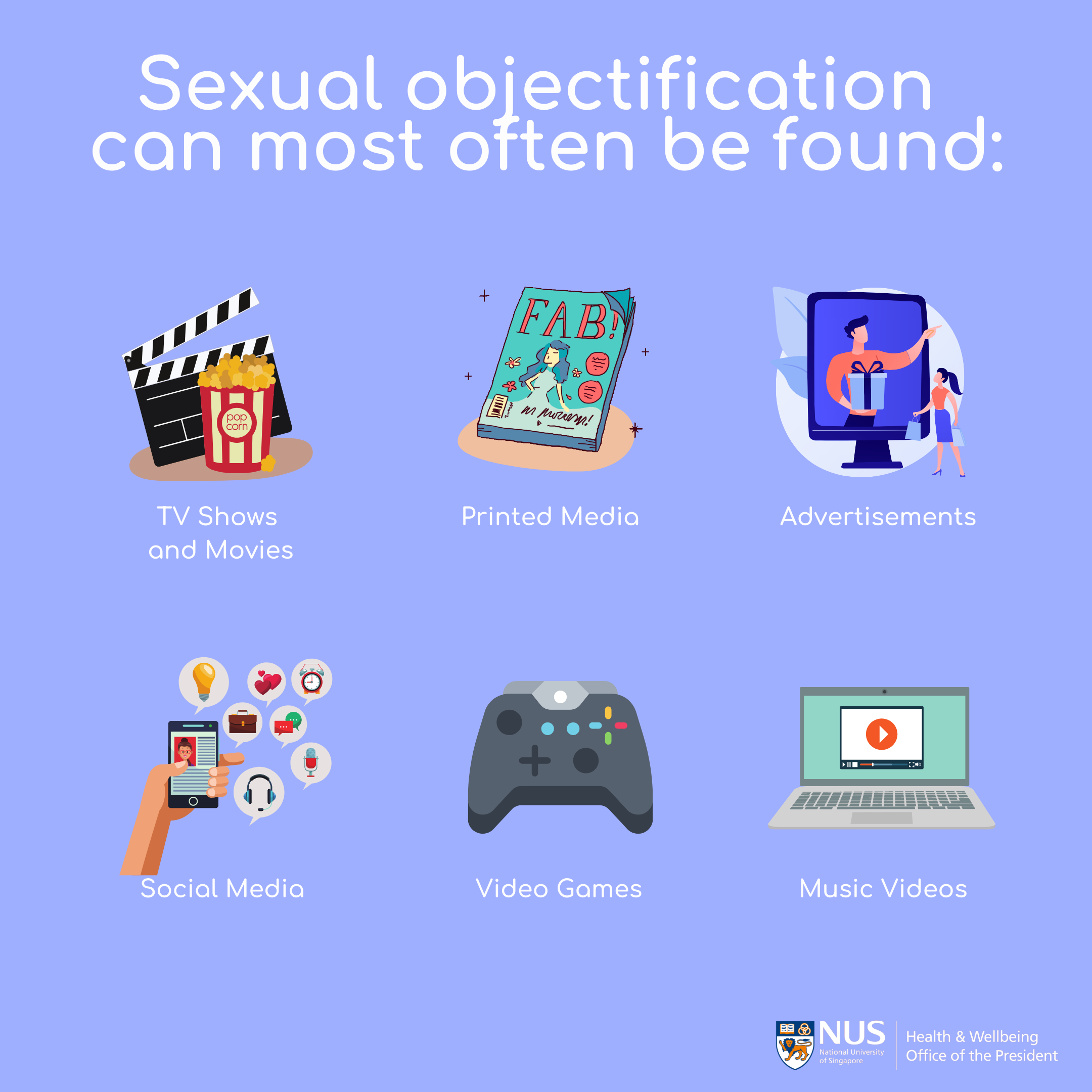

With sexual objectification primarily anchored on the visual appraisal of a woman’s appearance, it is no wonder that studies have found that more frequent consumption of media featuring sexualised women on television shows, magazines, social media and gaming, is associated with stronger support of objectifying women.

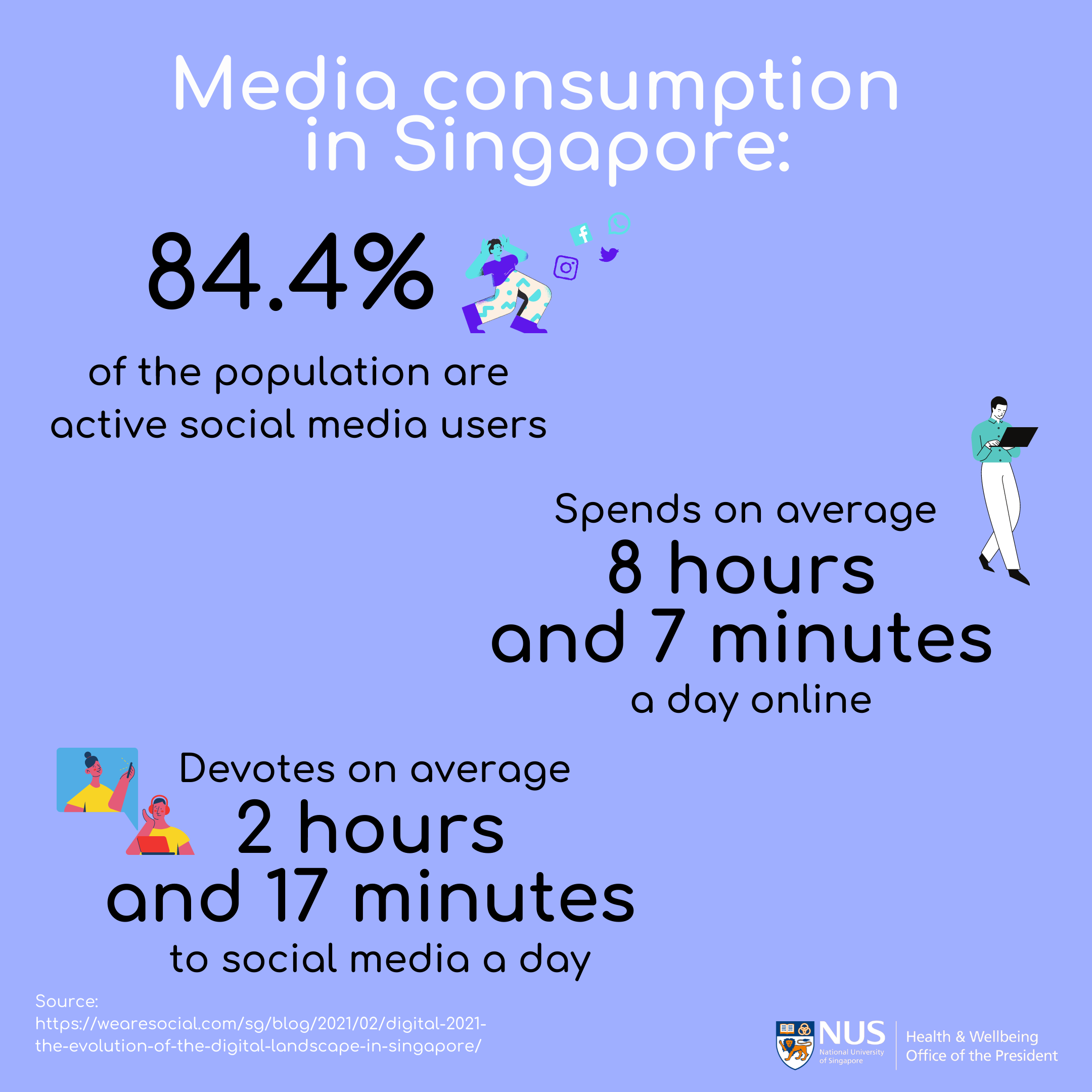

With the rise of the internet and social media consumption in Singapore, the sharing of information has never been easier. Social media platforms such as Facebook, YouTube, Instagram and TikTok have taken centrestage in perpetuating sexual objectification, creeping into our everyday lives unknowingly. According to Business Insider, a staggering 1.8 billion photos are posted in just a single day. A report by creative agency

We Are Social has meanwhile found that 84.4% of Singaporeans are active social media users, spending an average of 8 hours and 7 minutes online a day, with 2 hours and 17 minutes alone devoted to it.

A quick search on Instagram would show more than 70 million posts with the hashtag #fitspo — a word that combines “fitness” and “inspiration”. While fitness inspiration trends aim to motivate individuals to work hard on their fitness goals, some have critiqued this movement as harmful for reinforcing and internalising impossible body ideals. Indeed, studies have found that browsing Instagram for as little as 30 minutes a day was associated with higher levels of self-objectification — that is, when you start looking at your own body as an object and comparing it with societal ideals of attractiveness.

It’s not just imagery that contributes to sexual objectification. Comments, usually made anonymously, can contribute to sexual objectification as well. A study conducted by gender-equality advocacy group AWARE and technology firm Quilt.AI has shed light on the online discourse around gender-based violence in Singapore. The researchers studied 1,200 public social media posts across Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Reddit and Hardware Zone. Almost half of the comments online (48%) focused on belittling and objectifying women. Accounts owned by women on Twitter received twice as many misogynistic comments from others, and misogynistic comments were twice as likely to be “liked” and 4.5 times more likely to be re-tweeted when compared to non-misogynistic comments.

Why does all this matter?

Unsurprisingly, treating people and their bodies as objects can have negative consequences on mental health. While sexual objectification is played out in a virtual environment, the implications do translate over into the real world. In a 2016 study published by the British Psychological Society that used a smartphone app to gather ‘real time’ reports of sexual objectification, women reported being sexually objectified — most often by the objectifying gaze — approximately once every two days. The same study also revealed that women witnessed the sexual objectification of others at least once a day, demonstrating the prevalence of sexual objectification in women’s day-to-day life.

Exposure to sexually-objectified media can contribute to self-objectification where people become preoccupied with their physical appearances and criticise their bodies. Thoughts such as “How do I look? What will others think when they see me? Do I measure up?” may make people unhappy about their bodies. Such comparisons may breed feelings of shame and anxiety. These feelings may lead to myriad mental health difficulties such as depression and eating disorders. Women who witnessed sexual harassment via objectification may feel as though they are experiencing the harassment themselves. Prolonged exposure to sexual objectification is linked to insidious trauma, characterised by psychological (e.g. anxiety, depression) and physiological symptoms (e.g. headaches, hyperarousal, poor sleep) without overt trauma history.

More worryingly, exposure to sexualised media is linked to increased sexist beliefs and tolerance of violence against women. Women may see other sexualised women as less than capable and cast judgements about sexualised women. They may distance themselves from these sexualised women and blame women for their own sexual victimisation. For instance, 45% of the 1,000 respondents in a survey conducted by AWARE agreed that “women who wear revealing clothes should not complain if men make comments about their appearance.”

Learn what it looks like

Learn what it looks like

Sexual objectification comes in many shapes and forms. Sometimes, determining if the behaviour is inappropriate can be subjective, but if it makes you uncomfortable, it’s usually a good indication that it is. The first step to take is to educate yourself on what it is and what it looks like so that you can identify it if it happens. Here are common examples:

- Improper comments about your dressing or appearance: “That outfit is distracting.”

- Jokes about workplace advancements due to appearance, attractiveness, or dressing

- Being held back from a position due to appearance, attractiveness or dressing

- Catcalling, unwanted sexually-insinuating stares, or bodily evaluations

- Blaming you for an outcome or negative attention received based on appearance, attractiveness, or dressing

![]()

Culture cannot be changed overnight, and everyone has a part to play in creating a safe and supportive environment.

DISRUPT the cycle of self-shame

A common reaction to dealing with being sexually objectified at work is to self-stigmatise: “Maybe they are right, and maybe if I hadn’t responded, or dressed this way, it wouldn’t have happened to me; If I just ignore it, it’ll just go away”. There are also fears that we deal with: “What if I’m seen as a troublemaker if I flag this? Will I lose my job? Will it make things harder for me at work?”. It is key to understand that the problem of sexual objectification lies with the ones objectifying you, and not the other way around. The abuse has nothing to do with what you wore or did, or who you are. You did not bring this upon yourself, you are not to blame — and most importantly, you are not alone. Being constantly exposed to this and staying silent negatively impacts your mental health and perpetuates the problem and culture of sexual objectification.

Call it out when you see it and set clear boundaries

Ignoring the problem will not make it go away. Be brave! Respectfully point out that you do not appreciate such behaviour or comments, and that they are not appropriate. Don’t just call it out when it happens to you. Do it when you see it happening to others too. If we constantly highlight that a behaviour is unacceptable, this puts considerable pressure on people to re-think their behaviour. If you do not feel comfortable doing this directly, get someone to support you, such as a friend, trusted colleague or authority figure. As the saying goes, the culture of any organisation is shaped by the worst behaviour the leader and their team are willing to tolerate. Culture cannot be changed overnight, and everyone has a part to play in creating a safe and supportive environment. Start by setting clear boundaries and firmly communicating what is and is not acceptable behaviour. By working collectively, we can bring about change and create a safe and supportive community for all – by being an active bystander!

Take action

Document the incidents and build up your case. Find out about the resources available to you, such as the company’s policy on how to report this and support available to staff.

Check in with yourself

Finally, it is important to be mindful of how you have been or are being impacted by objectification. This can be a difficult, painful issue to navigate, and you do not have to do this alone. Suppose you are struggling to cope with its effect on your mood, identity, sexual behaviour and relationships. If so, we recommend seeking guidance from a therapist who has received specific training in sexuality and/or discrimination.

Respect and consent go a long way towards helping defray the issue with schools and workplaces setting frameworks, support, practices and policies to combat sexual harassment and sexual violence. NUS, for instance, has developed a compulsory module for all students and staff to raise awareness and educate the NUS community on an inclusive and respectful campus workplace culture. Knowing these potential effects of sexual objectification in media can equip us to better question and be aware of the media we consume. Everything we do shapes the experience of ourselves and others.

The authors/editors of this piece are: Ms Celeste Teo (Wellbeing Specialist Partner, Clinical Psychologist) (Main Author); Ms Justine Teo (Communications & Branding Manager); Ms Katherine Koh (Consultant, Organisational Psychologist); Dr Andrew Tay (Medicine ’07) (Director, Health and Wellbeing, Office of the President, NUS).

A department under the Office of the President, NUS Health & Wellbeing (NUS HWB) is built on the belief that each individual can be empowered to realise their own full potential in body, mind and purpose. Resources and information can be accessed on nus.edu.sg/hwb.