When Ties Run Deep

For celebrated alumna Ms Violet Oon (Arts and Social Sciences ’71), an association with the University spans across generations and is very much intertwined with her own family history.

Members of the Topsy Turvy Club at a party in 1948, with their wives and women college mates.

Members of the Topsy Turvy Club at a party in 1948, with their wives and women college mates.

When I was a teenager, my father casually commented one day as we drove through Club Street, “We used to live here when I was a child – my grandfather Mr Oon Cheng Lock used to gamble on behalf of the towkays in the Gentlemen’s Clubs along this street and he made good money.” Intrigued, I asked what that meant. My late father said, “You know, like Rhett Butler in Gone with the Wind – he kept 10 per cent of the takings.” He jested that it was the spoils of the table that put two sons through King Edward VII Medical School in the early 20th century. Was this true or false? I am not certain, but I much prefer this whimsical account, which entwines three generations of Oons – my grandfather, my father and I – with the long history of today’s National University of Singapore (NUS).

I think that few early families can lay claim to three generations of graduates from NUS, a family history spanning over 60 years. My grandfather Dr Oon Kock Tee (also known as Oon Kok Kee) and his brother Dr Oon Sim Kong graduated with Licentiates in Medicine and Surgery from King Edward VII Medical School in 1916 and 1917 respectively. Memories of my paternal grandparents were retold as tales from my father. “Your grandfather used to run a clinic at North Bridge Road, opposite the original location of Islamic Restaurant,” my father shared, “He was perhaps the only doctor who was unable to ‘make money’.” According to my father, my grandfather soon went on the high seas to become a ship’s doctor, leaving my grandmother in Singapore to fend for their growing brood of children on very little money. Whenever he docked back in Singapore, another baby was soon on the way.

In October 1928, my grandfather, who was part of the Chinese Medical Students’ Union, with 50 other doctors, all graduates of King Edward VII Medical School, attended a dinner in celebration of the 17

th anniversary of the Republic of China, at the then-Garden Club. This was featured in

The Straits Times.

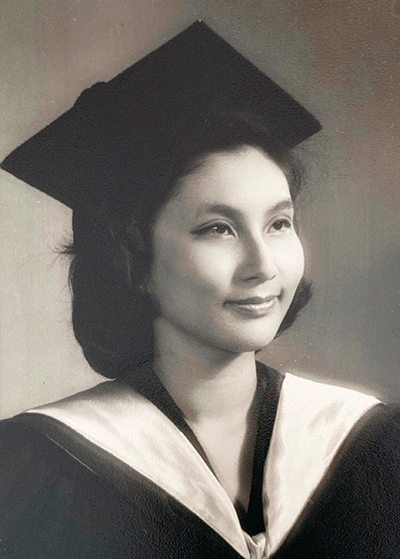

Ms Violet Oon’s gaduation photo, 1971.

Ms Violet Oon’s gaduation photo, 1971.

THE HALLOWED HALLS

The story continues when my father, Mr Oon Beng Soon (Arts ’46), entered Raffles College in 1939. Raffles College was the hallowed institute of learning of Singapore and Malaya when he enrolled as a student. In 1928, 43 students had enrolled when Raffles College opened. I discovered only recently that Raffles College produced a total of just 573 graduates from that enormous building at Bukit Timah Road. On 8 October 1949, Raffles College and King Edward VII College of Medicine merged to form the University of Malaya.

My father’s classmates — who included the late Mr Lee Kip Lee (Arts ’46), the father of Singaporean cultural icon Mr Dick Lee — skipped Final Exams due to World War Two. They were both later awarded War Diplomas in Geography from Raffles College.

Geography was my father’s favourite subject. One day, he nostalgically recalled, “Just before the fall of Singapore to the Japanese in 1942, the [then-]Head of Department, Professor Ernest Henry George Dobby, brought his favourite Geography students, Robert and I, to India to escape the Japanese.” My grandfather eventually passed away in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) in 1945. My father, then in India, brought the ashes of Dr Oon Kock Tee back to Singapore. The happy wanderer finally came home to roost. Was the love of Geography and wanderlust part of the Oon DNA? Perhaps. My father’s career as the first local executive in the Royal Dutch Shell company meant that his job brought us to many postings, from the neighbouring areas of Malacca, Kuala Lumpur and Jesselton (Kota Kinabalu today), to a posting in London in 1961. Although we looked forward to our moves as we traversed Britain, France and Spain, we always came home to Singapore.

Raffles College mates: Mr Oon Beng Soon (seated left); Mr Lee Kip Lee (seated on top of Oon Beng Soon, left), father of Mr Dick Lee; Mr Teo Cheng Guan (Arts ’46) (left standing), father of Senior Minister Teo Chee Hean; Dr Lim Kee Loo (Medicine ’49) (seated, far right), father of actors Mr Lim Kay Tong and Mr Lim Kay Siu. Photo courtesy of Mr Peter Lee, son of Mr Lee Kip Lee.

Raffles College mates: Mr Oon Beng Soon (seated left); Mr Lee Kip Lee (seated on top of Oon Beng Soon, left), father of Mr Dick Lee; Mr Teo Cheng Guan (Arts ’46) (left standing), father of Senior Minister Teo Chee Hean; Dr Lim Kee Loo (Medicine ’49) (seated, far right), father of actors Mr Lim Kay Tong and Mr Lim Kay Siu. Photo courtesy of Mr Peter Lee, son of Mr Lee Kip Lee.

My father and his friends formed the Topsy Turvy Club (TTC), and they had lots of fun and were up to hijinks while in college, just the way we would go on to have fun as students in the late 1960s. During World War Two, Raffles College was turned into a medical facility and was the Japanese army’s headquarters in Singapore, later reverting to a school of higher learning after their surrender. Two buildings stand sacrosanct in my own Singapore memories – King Edward VII College of Medicine, in the Singapore General Hospital grounds; and the Bukit Timah Campus, which was my father’s and my home for many years. It was a joyous day when the Bukit Timah campus was announced to be returned to the National University of Singapore in 2005, architecturally intact and where I had walked through the same hallways and quadrangles as my father.

What an exciting history my campus at Bukit Timah and my grandfather’s campus in the Singapore General Hospital grounds have had. They produced an admirable harvest of graduates — from doctors, to statesmen and heads of country mid-century — Mr Lee Kuan Yew (’41), our first Prime Minister, known as the father of modern Singapore; and the brilliant economist Dr Goh Keng Swee (Arts ’39), who served as Singapore’s second Deputy Prime Minister. There were also notable names across the pond, such as Dr Mahathir Mohamad (Medicine ’54), former Prime Minister of Malaysia, to a flowering of intellectual talent in the 1960s and 1970s – Ambassador Chan Heng Chee (Arts ’64), Professor Tommy Koh (Law ’61) and Professor Kishore Mahbubani (Arts and Social Sciences ’71), to name a few. The list goes on and on.

The students of our institutes of higher learning in Singapore not only had brains but also a deep capacity for, and interest in, the wider world. From the date that King Edward VII College of Medicine was launched in 1905 – our men and women showed that they were people of substance, from the interest of the doctors at the aforementioned 1928 meeting to celebrate the Chinese Republic till today. This is important to know as NUS has consistently pulled its weight to rise as one of the best universities in Asia, and in the world.

In 1971, following the footsteps of two generations before me, I graduated from the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences in the then-University of Singapore with a Bachelor’s degree in Political Science and Sociology, in spite of the fact that as a tribute to my father, I had taken Geography classes in my freshman year. While I loved it, I was unable to sustain my interest in the subject as my mind drifted off to sleep as soon as the curtains were drawn close, leaving the lecture theatre in darkness as the lecturer projected the slides on screen.

AN EMOTIONAL ‘HOMECOMING

The outdoor concert at SGH which Ms Oon attended in 2014, during her stay at the hospital.

The outdoor concert at SGH which Ms Oon attended in 2014, during her stay at the hospital.

King Edward VII College of Medicine is of special poignancy to me as I was warded at the Singapore General Hospital (SGH) for five weeks after suffering a stroke in June 2014. While being treated there with great care, I pondered each day, that just across the road was the college where my grandfather had studied to be a doctor, and I could channel his presence by my side as I slowly healed. This was where my grandfather had learnt to heal others with a similar affliction, and it is of great meaning and sentiment to me that my hospital of choice till today is SGH.

The College of Medicine Building, located within the grounds of SGH, resembles a classical Greek building, with a colonnade of 12 Doric columns, 11 large sculptured timber doors, and allegorical bas-relief sculptures depicting the teaching and practice of medicine (Teo, 2005 as cited in Tan, 2005). Above the central doorway is a Roman eagle crowned with a wreath, a classical symbol that signifies a civil or official building (Teo, 2005 as cited in Tan, 2005). I am also heartened to know that this hallowed building — which is part of the fabric of my family — has been conserved as a national monument and will always remain just the way it was on the outside, when my grandfather first walked through those doors.

When night fell, the hallowed edifice of Grecian columns opposite my hospital ward lit up, seemingly illuminated as a beacon of hope. One particular evening, there was a Mariachi band from South America which performed in the courtyard facing the Medicine building. As patients in wheelchairs, myself included, were wheeled into the courtyard, the band played to the background of the dramatically-lit College of Medicine. I wistfully recalled that my father loved the pulsating beats and sounds of Latin music. As I sat under the stars, enjoying music that touched his heart — against the backdrop of the medical school that my grandfather had studied in — I could feel the souls of three generations of Oons resonate in that starry, starry night.

Ms Violet Oon is a food critic, chef-restaurateur, consultant, cookbook author and authority on Peranakan and Singapore cuisine. Ms Oon first made her name as an Arts and Music Critic as well as a food columnist in the 1970s and was dubbed Singapore’s food ambassador by the Singapore Tourism Board in the late 1980s. She co-owns the Violet Oon Singapore group of restaurants. Her proudest moment came in 2019 when she was awarded the Lifetime Achievement for Outstanding Contribution to Tourism by the Singapore Tourism Board. Her life’s work has been to curate, collate and celebrate Singapore cuisine.