‘Natural’ By Design

By studying the history of Singapore’s flora, fauna and landscape, we stand to learn a lot about ourselves as a people. Environmental historian Associate Professor Timothy P. Barnard has unearthed some surprising insights on our collective history through his research.

The Singapore Botanic Gardens’ first Director, H.N. Ridley, in the Gardens’ jungle. Image courtesy of the Singapore Botanic Gardens.

The Singapore Botanic Gardens’ first Director, H.N. Ridley, in the Gardens’ jungle. Image courtesy of the Singapore Botanic Gardens.

From forest reserves, to the Botanic Gardens, down to the trees and other foliage planted along the roads, Singapore offers a meticulously-maintained pairing of its urban environment and the natural environment. Having nature so close to, and even within, the city is quite a wonderful thing and adds significantly to the quality of life Singaporeans currently enjoy.

It is this natural environment that fascinates Associate Professor Timothy P. Barnard, whose passion lies in teaching and examining the cultural and environmental history of Southeast Asia. His research in this area has seen him peeling back the layers of Singapore’s carefully-manicured gardens and nature reserves to uncover the stories of its historical environment and show how we have evolved and progressed as a society from colonial times to today. Assoc Prof Barnard also believes the environmental history of Singapore contains the stories of our society, embedded in the flora and fauna of locations such as the Singapore Botanic Gardens. And this is where he has a surprise for us all: Singapore’s natural environment is not natural at all.

Environmental History 101

We all know history as the study of past human interactions on a macro level. Most of us would see history as a record of what a particular nation or people did, to or with whom, and when. Environmental history takes this a step further and studies the interactions between humans and the natural world over time, seeing how we influence our environment, and how the environment influences us.

Environmental history is a comparatively new discipline, having emerged from the environmental movements of the 1960s and ’70s in the United States. It is perhaps fitting then that an American would be the one to dig deep into Singapore’s natural past; Assoc Prof Barnard is a Permanent Resident of Singapore and has been at NUS since 1999.

By any measure, he is pleased to be exercising his passion here. “Singapore is a wonderful place to study environmental history, because we have a nice starting point that is well-documented, that being 1819, when the British arrived,” he shares. “They kept archives and records of everything, from temperature and the amount of forest cover to the types of animals present at the time.”

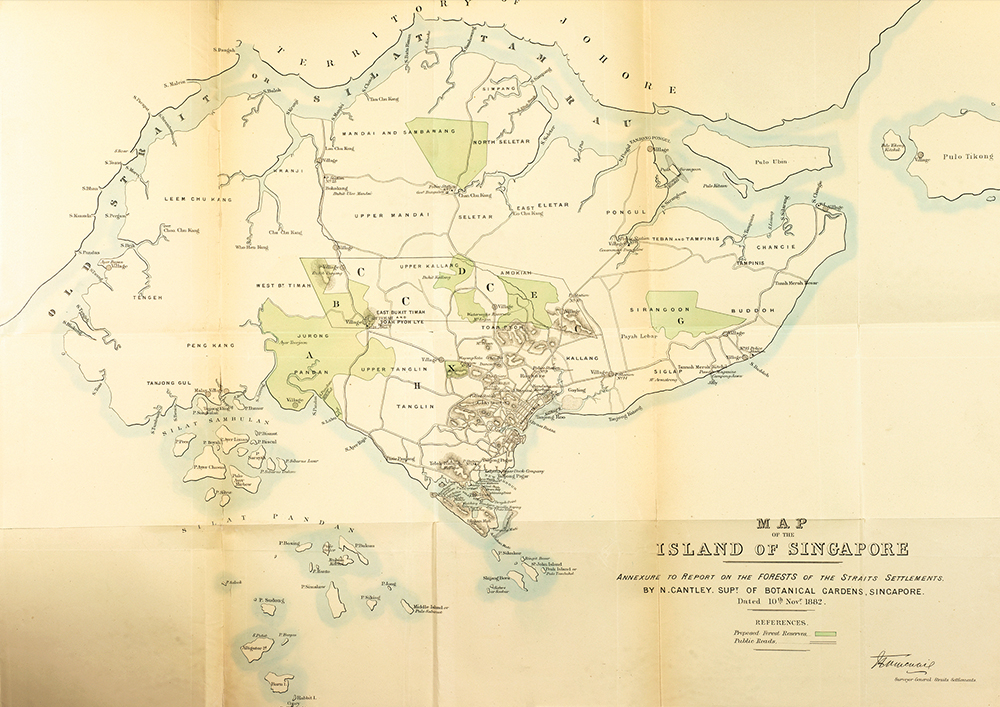

An 1883 map indicating the forest cover in Singapore. It shows that less than 10 per cent of the island was covered in forest. This was a huge environmental problem.

An 1883 map indicating the forest cover in Singapore. It shows that less than 10 per cent of the island was covered in forest. This was a huge environmental problem.

The impact of Imperialism

When the British led by Raffles claimed Singapore for ‘King and Country’, it was the beginning of a new era for the island. But the real changes to the environment would start once the British East India Company (EIC) took over in 1824. The island at the time was heavily forested and occupied by just a few thousand inhabitants. Being a company (and the largest in the world at the time), the EIC was in the business of generating profits. The profitable commodities of the colonial era came from plants: be it tea from China, nutmeg, cinnamon, cloves, chilli or cotton, it was agriculture that made the business world go around. Driven by profits, the British turned the island into one large plantation. Workers cut everything down to plant their crops, mostly pepper, gambier, coffee and cotton, irrevocably altering the flora and fauna of the island. As such, the island was almost completely stripped of its original environment and dotted with farms and plantations by the time it achieved independence in 1965.

Singapore then underwent extensive reforestation projects, a result of the government’s efforts to make the island a more liveable place, resulting in the Singapore we know today. “Singapore was over 90 per cent deforested by the 1880s,” Assoc Prof Barnard reveals. “By reforesting it, we changed the environment,” he says. “Then, we put in the plants to fit our needs, and also chose the animals to come in — everything from dogs to horses to cows to pigs to pet animals; whether they be songbirds or the fish that are in our waters.”

Singapore was over 90 per cent deforested by the 1880s. By reforesting it, we changed the environment. Then, we put in the plants to fit our needs, and also chose the animals to come in.

Associate Professor Timothy P. Barnard

Created and Curated

This planned reforestation created a landscape very different from what it originally was 200 years ago — and this was what Assoc Prof Barnard meant when he said that Singapore’s natural environment is ‘not so natural’. “It’s one that was created and planted. In a sense, the hands of man shaped it and made it.” To illustrate the extent of its created — and curated — nature, he cites an obvious feature of our ‘City In a Garden’: “Did you know that the National Parks Board theoretically knows where every single tree in Singapore has been planted and exists? That to me is quite an interesting state of affairs.”

One example he likes to use of this ‘creation of nature’ is that of the Botanic Gardens, its connection to colonialism and its role in Singapore’s history. Originally situated on Fort Canning Hill, the Botanic Gardens was not meant as a leisure destination — it was established to find new ways to plant or cultivate crops here that would make money, because that was what the EIC was after. The taming of rubber, an agricultural success story, took place mostly at the Botanic Gardens. “In each era of the Botanic Gardens’ history, it has played a role that was important economically,” says Assoc Prof Barnard. “The ultimate example (of cash crops) of course is rubber. The development of rubber is one of the most important events in the last 150 years. It transformed the environment in Singapore and other countries in Southeast Asia, when the British brought in labour to work those plantations.” He adds that money from rubber also created a lot of the future economic leadership of Singapore.

Yet this familiar landmark could have ended up as a footnote in history. “The Botanic Gardens was left behind once we became independent, as it was seen as a colonial institution, and was only revived in the 1990s,” Assoc Prof Barnard explains. “It’s now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, so it’s not going anywhere, but the key thing to me was how intimately connected it is to the economy, the government and Singaporean society, throughout our history.”

Working alongside Botanic Gardens Director Nigel Taylor, which included on-site lectures for history modules, Assoc Prof Barnard realised the Botanic Gardens represents a microcosm of Singaporean society as a whole. The extensive planning that went into the Gardens reflects the wider Singaporean society, how it is meticulously planned to achieve a certain set of objectives. The Gardens is far removed from its original colonial-era purpose of crop research, and now serves to provide Singaporeans a liveable urban environment — one he calls a “pleasant place, but planned and designed for specific purposes”.

Finding Meaning in Myth

While history lies at the core of what Assoc Prof Barnard does, he views the way it is taught nowadays as simply being a litany of dates, names and events, to be regurgitated come examination time. What matters more are the deeper meanings of these events, and the lessons that can be extracted from them. This has led him to examine Singapore’s past from the aspect of the island’s mythology. The legend of the ‘swordfish that attacked Singapore’ resonates with him, as it reflects a traditional Southeast Asian way of telling stories, and also involves animals and how they can shape human society.

An example he points out is a perennial pest, the mosquito. The urban development of Singapore actually took into account whether it was malaria or dengue that was the disease threat of the day. Pets also influenced the direction of society: when pedigree dogs were introduced to Singapore in 1884, rabies became a problem on the island, as dogs had previously not existed here. This led to a range of local regulations and ordinances in an attempt to limit the spread of the disease, which had their impact on 19

th-century Singaporean society. “If you hark back to those original stories, like the lion [that Sang Nila Utama allegedly encountered] or swordfish, they are also interesting ways to convey basic principles about the society, or about what was going on at the time.”

Assoc Prof Barnard continues to impart his knowledge of Singapore and the region to students in his lectures, consisting of introductory modules on Asian history as well as upper-level ones on the Malay world, environmental history and film. “I want to recreate [the knowledge] through similar stories that we can understand on modern times, so we can think of Singapore in new ways,” he says.

A Fishy Tale

A Fishy Tale

In his book

Imperial Creatures (2019), Assoc Prof Barnard recounts the tale of Singapore being attacked by swordfish (

Singapura Dilanggar Todak). One day, swordfish began spearing people on the shore, so the ruler sent his soldiers to deal with it. Unfortunately, they suffered many casualties without having much effect. Seeing this, a smart young man suggested using the trunks of banana plants. The ruler agreed and the swordfish speared the trunks and got stuck. But the ruler became jealous of the young man and had him killed. Assoc Prof Barnard sees this as a symbolic story, about the attitudes of the ruling class and their reaction to change and threats, in the wake of the fall of the Kingdom of Singapura and the flight of its rulers to Malacca.