Rethinking care in a fast-ageing society

Researcher and NUS alumna Susana Concordo Harding (Public Policy ’09) explores how to tackle the gender disparity and perceptions of caregiving as Singaporeans age, in the wake of her recent WoW: Ignite talk held on 8 March 2023.

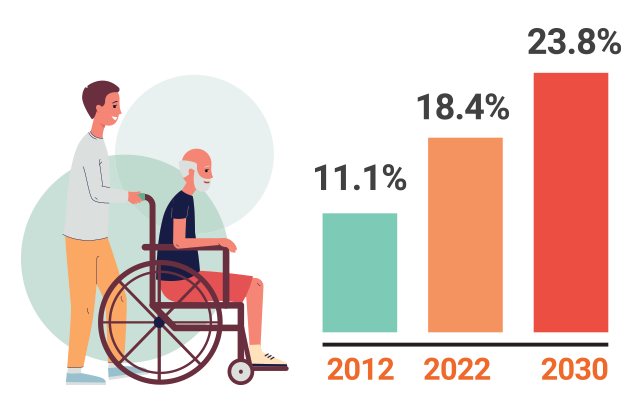

Singapore is among the fastest-ageing nations in the world. An estimated one in four Singaporeans will be aged 65 and above by 2030. However, not everyone is ageing well. While life expectancy has gone up, many people are spending a significant part of their lifespan in poor health due to chronic disease and disability.

This means many of us will take on caregiving roles for our loved ones, even as we grow older and require care ourselves. So what can individuals and society do to minimise the challenges associated with growing old? How can we reshape the caregiving experience and enhance its positive aspects so it becomes more satisfying, rewarding and meaningful?

Ms Susana Concordo Harding, Senior Director at the International Longevity Centre Singapore by Tsao Foundation, addressed these hard questions in an interview with The

AlumNUS, following her recent

WoW: Ignite talk titled “Insights into Caregiving Transitions: Towards Positive Caregiving Experiences and Resilience”. Drawing insights from local research and her policy and advocacy work in successful ageing, Ms Harding unpacked key factors that contribute to positive caregiving trajectories and suggested interventions that could benefit caregivers in the community. Much of her research centres around older women, who bear the brunt of the caregiving load even as they age and grapple with declining health.

AN AGEING SOCIETY

The proportion of Singaporeans aged 65 and above is rising rapidly.

Source: Population in Brief 2022, September 2022

Source: Population in Brief 2022, September 2022

MIND THE GENDER GAP

Research shows a gender disparity in ageing and caregiving, and women are at a higher risk of facing isolation, financial challenges and lack of support as they grow older, said Ms Harding, who is also the Honorary Secretary of the Board of Directors at Centre for Seniors, a non-profit social service agency dedicated to helping seniors remain meaningfully engaged.

Citing the

Caregiving Transitions among Family Caregivers of Elderly Singaporeans (TraCE) study by the Centre for Ageing Research and Education, she highlighted large gender gaps in caregiving roles. For example, women make up three in four caregivers; the mean caregiver age is around 62 years old; and two-thirds do not hold full-time jobs — either they are not working, have already retired or work part-time. A third of caregivers also report clinically significant depressive symptoms.

Ms Susana Harding tackled the issues of caregiving in Singapore at her WoW: Ignite talk on 8 March 2023.

Ms Susana Harding tackled the issues of caregiving in Singapore at her WoW: Ignite talk on 8 March 2023.

“Data like this clearly shows a strong gender dimension to ageing,” said Ms Harding. “With women living longer, it means the burden of caregiving falls on them. When they need care themselves, what happens?”

Gender inequity in caregiving also has socioeconomic ramifications. Recalling her encounter at the

WoW: Ignite talk with an attendee, who stopped working to care for her late mother with Parkinson’s disease, Ms Harding said it is not uncommon to see caregivers give up their full- or part-time jobs due to disrupted schedules — losing their self‑esteem and identity along the way.

“The current cohort of caregivers becomes increasingly vulnerable,” she explained. “They end up being out of the labour force, and when their care recipient passes on, they have to rebuild their lives. It can be very difficult for them because they may lose their self-esteem and confidence as they have been on the margins of their social network while providing care all this time.”

![]()

With women living longer, it means the burden of caregiving falls on them. When they need care themselves, what happens?

Ms Susana Concordo Harding, (Public Policy ’09)

A SILVER LINING

But it need not be this way. On changing the perception that caregiving is primarily a woman’s job, Ms Harding said, “Society’s expectations are not cast in stone and can evolve and change. But we need to start somewhere and continue to advocate for changes to happen. It’s up to everyone to make it happen collectively.”

While the caregiving discourse tends to focus on the negatives, such as disrupted work schedules, financial strain and burnout, Ms Harding said caregivers report several positive aspects too. These include fulfilment in being filial, reciprocating care, being a role model to future generations and gaining knowledge about ageing, she said, citing data from the Qualitative Insights into Caregiving Transitions (Quali-T) study by Duke‑NUS Medical School.

Caregiving in Singapore, by the numbers

- 73.4% of caregivers are women.

- 1/3 of caregivers report clinically significant depressive symptoms.

- Informal primary caregivers spend 29.3 hours a week — or about 3.5 days of work — juggling caregiving responsibilities. Unlike formal caregivers, who are professionals paid for their work, informal primary caregivers care for and assist a friend or family member without pay.

“We are so used to looking at the negative aspects of caregiving that we don’t see there are also benefits — it’s not just a burden,” said Ms Harding. “There are benefits (of caregiving) even in the dissatisfied group of caregivers, a sense of doing it for filial piety.” (See ‘The 4 Types of Caregivers’ below.)

SHARING THE LOAD

Based on data collected, Ms Harding suggested several strategies to support caregivers. At the clinical level, healthcare teams could actively engage and involve caregivers when developing care plans for patients. For instance, a nurse clinician could start a conversation with the caregiver while the care recipient is being treated by his or her doctor, a nurse.

“The idea is to get to know the caregiver, build a relationship, provide some health education in the process and detect the risk of breakdown of care and caregiving burnout early,” said Ms Harding, adding that Tsao Foundation may soon pilot such a practice in its clinics and services. At the same time, caregivers would do well to build up their emotional resilience and incorporate self‑care into their daily routines.

The 4 types of caregivers

The Qualitative Insights into Caregiving Transitions (Quali-T) longitudinal study by Duke‑NUS Medical School looked at the subjective life experiences and caregiving trajectories of caregivers in Singapore.

It identified four types of caregivers:

- Balanced: Low burden and moderate benefits.

- Satisfied: Low burden and high benefits.

- Dissatisfied: Moderate burden and low benefits.

- Intensive: High burden and high benefits.

Ms Harding also suggested rethinking caregiving as solely a family responsibility, particularly for those who do not have families of their own or get little family support. In such situations, individuals could build their “family of choice” — a group of people who are not biologically related but who band together for ongoing social support. “Not all of us will have a family to care for us. Data shows a growing number of singles. Who will take care of them? Some of us will need to start building our family of choice.” An example might be friends pooling resources to live together or near one another, she said. Or it might include co-workers, neighbours, old school connections or familiar people in the neighbourhood, who look out for the person requiring care.

Last but not least, Ms Harding also hopes to look into ways to support and engage more men to take up caregiving roles. “It may not mean having a 50-50 (caregiving load between men and women) — it could be negotiated — but the conversation needs to start now. At this moment, we could say we want to change, that caregiving shouldn’t just be a woman’s role. Everyone should be given a chance to say, ‘I want to be a caregiver’.”