STRIKING A BALANCE

The first port of call for many seeking an ethical approach to tech is regulation and laws. But these must strike a delicate balance. Premature or sweeping regulation — such as outright bans of specific technologies — risks stifling the benefits of tech advancements. On the other hand, allowing technology to go unfettered is not a feasible option either.

To Prof Chesterman — the former dean of the NUS Faculty of Law and the Co-President of the Law Schools Global League — this may not involve tearing up current laws and drafting new ones. “Most laws can already cover the use of new technologies, especially AI, although a few areas need new rules,” he says.

He points to potential regulations surrounding autonomous vehicles. Would these require a new set of road traffic rules? Probably not, he says. They would have to be updated to take into account the unique features of driverless cars. “So you would have to adapt your rules and work out new ways of applying them,” adds Prof Chesterman, who has explored these issues extensively in his book,

We, The Robots? Regulating Artificial Intelligence and the Limits of the Law.

Beyond the law, society can also enjoy a more positive relationship with tech if it adopts three guiding principles, wrote Prof Savulescu, one of the world’s foremost scholars in the field of biomedical ethics. He proposes three principles: Think First, Take Responsibility and Act Ethically. This approach builds on society’s ability to question assertions and assumptions and accept the responsibility of using new technologies.

![]()

ChatGPT is just coming up with predictions on what the next block of text is, based on huge databases of past text. But some people don’t realise this and think of the tool as possessing human-level intelligence — which it does not.”

Prof Simon Chesterman, Senior Director of AI Governance at AI Singapore

Before ethical conversations can take place, people need to get a good grasp of the subject matter they are studying. But understanding can sometimes be lacking in conversations about complex technologies like AI. “Take ChatGPT, for example,” Prof Chesterman highlights. “People don’t understand that it’s essentially a probabilistic engine. It’s just coming up with some predictions on what the next block of text is, based on huge databases of past text. But some people don’t realise this and start to think of the tool as possessing human-level intelligence — which it does not.” Thus, he believes that when we have conversations about the ethics of technology, it is important that we focus on the ethics of the people who are

programming the technology because they can have a big impact on the technology’s ethics.

Knowing what is ethical and what’s not is not enough. There also has to be an understanding in society that ethical breaches are not acceptable. This has played out in the business world, where some people are beginning to think that human intelligence can be replaced with AI to make decisions, according to Professor David De Cremer, Director of the Centre on AI Technology for Humankind (AiTH) at the National University of Singapore Business School. If left unchecked, these algorithms could be used to fire staff, a phenomenon known as robo-firings. But as Prof De Cremer stresses, machine intelligence has no intuition and consciousness. “This approach means that people have to work in very consistent ways. But sometimes, as a human, you have a bad day or a good day,” he points out.

Businesses should be aware of such nuances before rushing to adopt technologies. Set up in 2020, the AiTH aims to champion such views in the business community. Through such efforts, it hopes to build a human-centred approach to AI (HCAI) in society. HCAI designs AI systems with the understanding that intelligent technologies are fully embedded in society. Such systems can therefore be expected to act in line with the norms and values of a humane society, including fairness, justice, ethics, responsibility and trustworthiness. HCAI also preserves human agency and a sense of responsibility by designing AI systems that give users a high level of understanding of, and control over, their specific and unique processes and outputs.

Those working at the front-end of technology development realise that what they’re doing is cutting-edge and could change the world. And they’re asking for a little help in trying to maximise the chance that it changes the world for the better and not the worse.

Prof Simon Chesterman,

on the tech industry’s approach

to ethics

PUSHING THE BOUNDARIES

Ethics is an especially dicey issue in the world of computing and tech. Professor Jungpil Hahn, Vice Dean, Communications, at the NUS School of Computing, highlighted this in a 2021 lecture, where he observed that for many new technologies, there was no good way to balance the harms against the benefits since many of the harms are unknown, unquantifiable or unpredictable. There is also a lack of consensus about the correct ethical approaches to technology. So it is important that Singapore and her institutions — including NUS and AI Singapore — remain at the forefront of governance debates, adds Prof Chesterman, who is also Dean of NUS College. Prof Savulescu agrees, saying that power comes with responsibility. “The decision to do nothing accrues responsibility when action is a possibility.”

DID YOU KNOW?

ChatGPT is the largest language model created to date. It has 175 BILLION parameters and receives 10 million queries per day.

Source: InvGate

To achieve this, AI Singapore is pumping resources into research about whether we should trust AI; the circumstances in which humans will, in fact, trust AI; and strategies to ensure that it is safe and accountable. In this way, efforts to build a consensus around the ethics of tech are picking up speed. But Dr Reuben Ng, from the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy (LKYSPP) and the Institute for the Public Understanding of Risk (IPUR), cautions against making ethical considerations an afterthought. Dr Ng, who used to work in the tech sector, has seen how doing so can hamper the development of ethical tech products. He tells The

AlumNUS, “In the tech world, there’s a saying that ‘done beats perfect’, which suggests that its focus was on developing a working product, rather than prioritising security and privacy.”

Even more worrying is when developers deliberately design a product or service unethically. Take excessive screen time in childhood, which has been linked to health problems, including a higher risk of obesity and reduced cognitive development. Behavioural design specialists have made it nearly impossible for kids to put down their phones. They use simple hacks, such as continual notifications and prompts to trigger regular engagement, which can be used for other purposes, such as advertising and marketing.

![]()

IN THE TECH WORLD, THERE’S A SAYING THAT ‘DONE BEATS PERFECT’, WHICH SUGGESTS THAT ITS FOCUS WAS ON DEVELOPING A WORKING PRODUCT, RATHER THAN PRIORITISING SECURITY AND PRIVACY.”

Dr Reuben Ng, Assistant Professor, Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy

Dr Ng has saw this himself when he was put in tight spot. “I was working on a project that pricked my conscience — it involved increasing the stickiness to a harmful product,” shares Dr Ng. “It was a directive beyond my pay grade, and I was caught in a situation where whistleblowing might attract retaliation.” He eventually left the project because of the moral dilemma he faced.

It should come as a good sign, then, that discussions around ethics are increasingly being driven by the tech industry itself, because ethics in tech is not just for the good of society — it can also be good for business. “Today’s consumers are increasingly discerning, are aware of risks and want to be shielded from them,” Prof Chesterman explains. “If you could confidently say your product was ethical or exhibited good governance, that wouldn’t just help avoid problems with regulators or your own moral conscience. It could also be a selling point to consumers. I’ve not had anyone in the AI space say, ‘No, we want less governance.’ If anything, they want more.”

Behavioural scientist Dr Reuben Ng advises against considering ethics as an afterthought.

Behavioural scientist Dr Reuben Ng advises against considering ethics as an afterthought.

Consumers are not the only ones clamouring for more ethical practices and behaviours; employees are also making their voices heard. This is probably because of a growing realisation of the importance of ethics, thanks to a shift in the way ethics are taught in school. These days, ethics is no longer taught in a conceptual manner. Instead, teachers ground these ideas in practical and applicable ways. For instance, Dr Ng tries to make ethics come alive in his classes at LKYSPP through immersive roleplaying activities and policy exercises. “It can’t be a dry, conceptual exercise,” as he puts it. That way, students see how ethics can be used in real-world scenarios, which they can then apply when they enter the working world.

RECOMMENDED READS

Keen to sink your teeth into the intersection of ethics and nascent technologies like AI? Here are some handy books:

The Black Box Society: The Secret Algorithms That Control Money and Information

by Frank Pasquale

The Age of Surveillance Capitalism

by Shoshana Zuboff

Artifice

by Prof Simon Chesterman

A CONTINUING CONVERSATION

The world of biomedical sciences has long been subject to strict ethical regulations, given its potential impact on human life. But as Prof Savulescu pointed out, there are still some thorny issues that the industry needs to address. Some of these — such as the balance between personal liberty and social responsibility — were brought to the fore by the pandemic.

But other medical trends have thrown up yet more issues, Prof Savulescu noted. “Antimicrobial resistance has the potential to make once‑beaten diseases deadly again. The maintenance of effective antibiotics requires international collective action. Does the patient’s best interest demand the best available care now or the collective protection of antibiotic efficacy for the future? These are decisions we will need to make in the clinic, nationally and internationally, as antibiotics are a communal resource.”

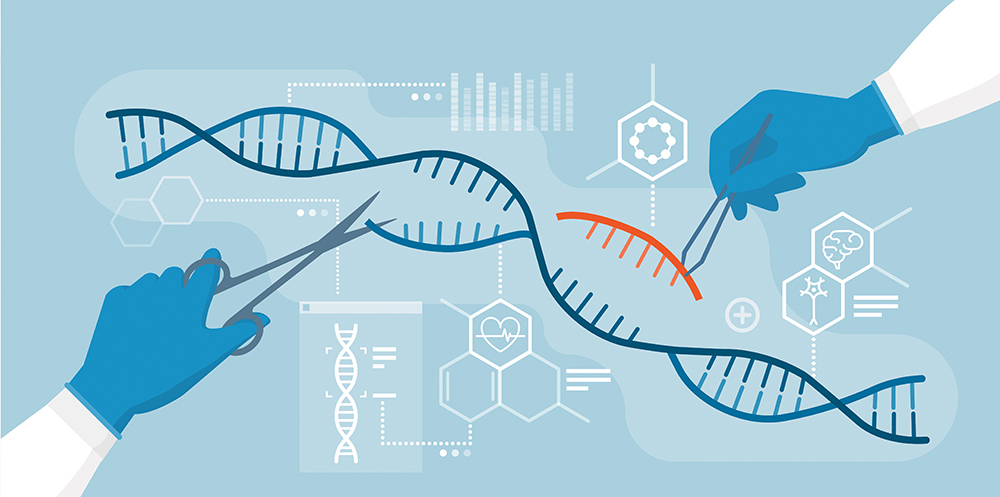

The unleashing of new frontiers in medicine has raised novel issues as well, said Professor Chong Yap Seng (Medicine ’88), Dean of NUS Medicine, and Lien Ying Chow Professor in Medicine. “With the rapid and continuing advances the world has made in genomics, precision medicine, big data and AI, we now have an unprecedented opportunity to drastically improve people’s lives with new health approaches and technologies.” Prof Chong added that in order to reap these benefits, however, the ethics of today must be updated. We must also address structural and social factors that increasingly contribute to disease, such as limitations of access and social disadvantage.

![]()

With the rapid and continuing advances the world has made in genomics, precision medicine, big data and AI, we now have an unprecedented opportunity to drastically improve people’s lives with new health approaches and technologies.

Prof Chong Yap Seng, Dean of NUS Medicine, and Lien Ying Chow Professor in Medicine

One such issue is the development of organoids, a tissue model of various organs made from stem cells. Expounding on their benefits, Prof Savulescu said, “They can model diseases and help find and test new treatments for some of the most intractable diseases. Scientists have transplanted human brain cells into the brains of baby rats, offering immense possibilities to study and develop treatment for neurological and psychiatric conditions. But what is the moral status of these new life forms?”

These issues are being deliberated and debated at the Centre for Biomedical Ethics (CBmE) at the NUS Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, one of the largest academic research centres for bioethics in Asia. Summarising his team’s work, Prof Savulescu explained, “Our goal isn’t to tell you what to think, but to support effective, responsible, goal-oriented discussions to help us understand the costs and benefits of the decisions we make in healthcare as patients, caregivers, institutions and policymakers.”

Research is a key plank of CBmE, with platforms that study clinical, health system and public health ethics; regulation of emergent science and biomedical technologies; and research ethics and regulation. It aims to generate outputs that are relevant to policy and accessible to a broad base of professional, academic and non‑academic communities.

In addition to everyday bioethical issues, the Centre also examines groundbreaking and novel areas where such issues may arise — including space exploration. For example, this July, it will lead a global discussion on bioethical issues that may occur from space travel through the Centre’s first-ever short course on the matter. It targets space industry operators, as well as those from research, education and medicine who have an interest in bioethics, critical thinking and space medicine. The course introduces learners to bioethical issues that may emerge when humans venture to outer space for short and long durations. Various ethical frameworks will be used to address the impacts of spacefaring on the physiological and psychological aspects of human well‑being as well as concerns arising from the modification of humans for space and of extraterrestrial environments for human habitation.

EVERYONE, EVERYWHERE

Ethical considerations cannot be properly appreciated in silos, which explains why the University is such a proponent of cross-border and cross‑disciplinary conversations about the matter. For one, the CBmE space travel discussion is designed to be global, with the Centre sponsoring up to five participants from low- and middle-income countries and tertiary students from around the world. Beyond spaces for discussion and deliberations, there also need to be avenues for redress. Dr Ng — who felt that there were none for fellow engineers like him when he was working in tech — is leading the charge on this front. He is now collaborating with other professionals to build a global whistleblowing platform. “This would make it easier for anybody to report and hopefully raise awareness on unethical practices,” he says.

Perhaps this ties back to an enduring principle of ethical tech use: That it must be inclusive to all. Having more stakeholders may sometimes be viewed as inefficient since disciplines can have conflicting interests and views on ethics, which can slow the process. But if the past few years have taught us anything at all, it is that cooperation and coordination bode much better for the world than isolation.

Text by Roy Sim

IN A NUTSHELL

Ethics in technology — as summarised by ChatGPT:

Ethics in technology refers to the principles and values that guide the development and use of technology in a way that benefits society while minimising harm. It involves considering the impact of technology on individuals, communities, and the environment, and making decisions that prioritise the well‑being of these stakeholders.

Ethics in technology refers to the principles and values that guide the development and use of technology in a way that benefits society while minimising harm. It involves considering the impact of technology on individuals, communities, and the environment, and making decisions that prioritise the well‑being of these stakeholders.

Some key ethical issues in technology include privacy, security, accountability, transparency and fairness. For example, technology companies must consider how they collect and use personal data, and how they can ensure the security of that data. They must also be accountable for any negative consequences of their technology, and be transparent about how it works and how it is used.

Overall, ethics in technology is about creating and using technology in a responsible and socially conscious way, with a focus on maximising the benefits while minimising the harm to individuals and society as a whole.

The above should give you a sense of how powerful tools like ChatGPT can be. That is because the three paragraphs you just read were written by the tool after we gave it the simple prompt, “Tell us about tech and ethics”. All this text was generated in under 20 seconds, suggesting that generative text might be the way of the future. Of course, such tools are prone to inaccuracies, so do not just take their word as the truth.